Blue Prince and Puzzle Friction

The same friction that makes a game frustrating at hour 2 can make it addictive at hour 20.

Like many of my colleagues, I’ve spent the last week or two lost deep in the most recent indie darling, Blue Prince, a mystery/puzzle game about inheritance and unreliable architecture.

At first, I was a little nonplussed. Maybe I’ve consumed too much surrealist art, but at first I was disappointed at how mundane the setting was: “A house that rearranges itself around you, but it’s not an existential horror and/or multilayered magical-realist metaphor? How dull!”

A little more playing and I was frustrated with how brutal the randomization could be for me as I just tried to put together enough rooms and keys and gems and whatnot to even explore half of the house. I even went so far as to tell coworkers I was probably going to stop playing after one last run or two.

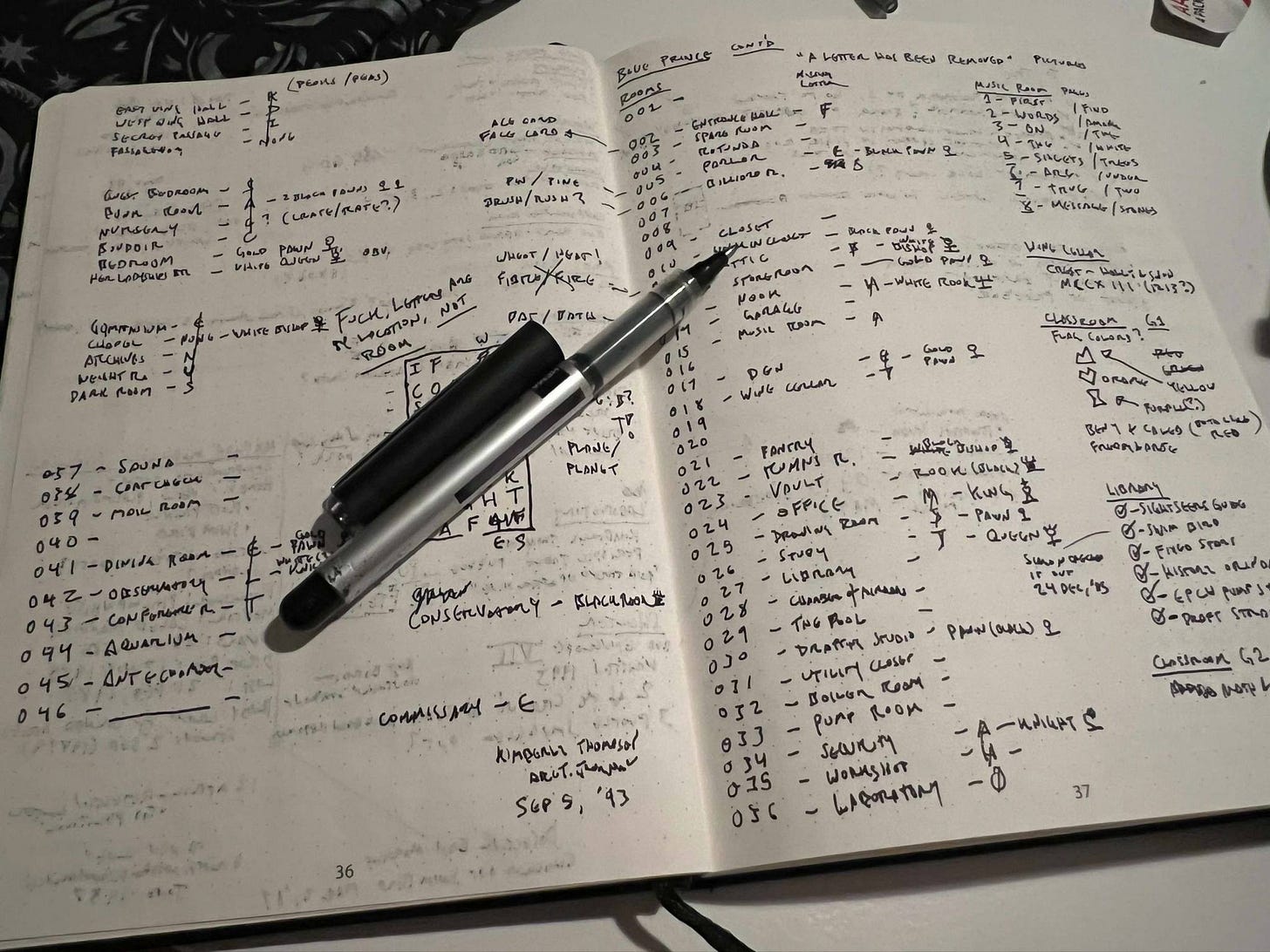

And then, before I knew it, I had filled 12 pages of my notebook with notes and borderline Pepe-Silvia-level scrawl and theorizing, solved countless puzzles, and only given up to look up a solution once or twice. By this point, it’s fair to say that the game hooked me hard.

Now, there’s no shortage of other game-adjacent media writing about the game’s success, or its mysteries, or even how it seems to drive away some players while absolutely addicting others. And that’s all well and good, of course. Any good piece of art is going to provoke a fair amount of discussion and consideration. The game doesn’t need me proselytizing for it, and I hope its developers are celebrating their well-earned hit.

But after nearly 60 hours of playing, what I do want to discuss is the nature of BP’s gameplay and how its weird mashup of “roguelike” and “puzzle game” results in an experience that can be offputting for many at first, but deeply addictive to those it does hook. Because it’s a counter-intuitive twist on some basic assumptions about gameplay, and one that I think we’ll see other games attempt to emulate in the future.

Warning, this article will contain some very light spoilers: I won’t give any big plot revelations, nor spoil any big puzzles, but with a game like this, some of the joy in playing is learning about the existence of a puzzle where you didn’t realize there was one. In the process of explaining the gameplay effects, I may have to give some concrete examples about items, rooms, and puzzles that you might otherwise expect to discover on your own within the first 10 hours or so.

If you haven’t played the game yet and you intend to do so, go do that first. Then come back after two hours if it hasn’t hooked you — or after thirty hours if it has.

What is Blue Prince?

First, an explanation for those who haven’t played the game.

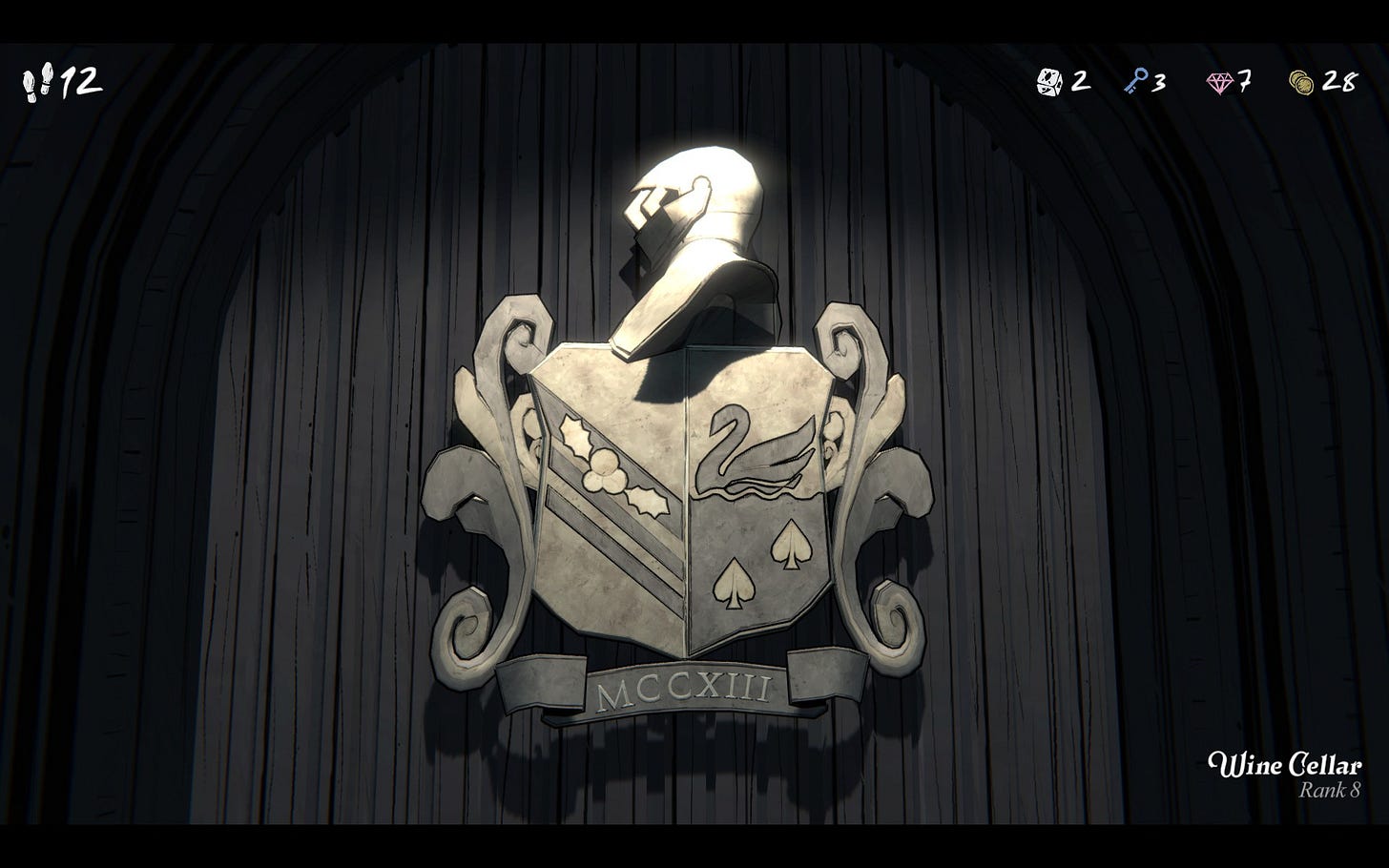

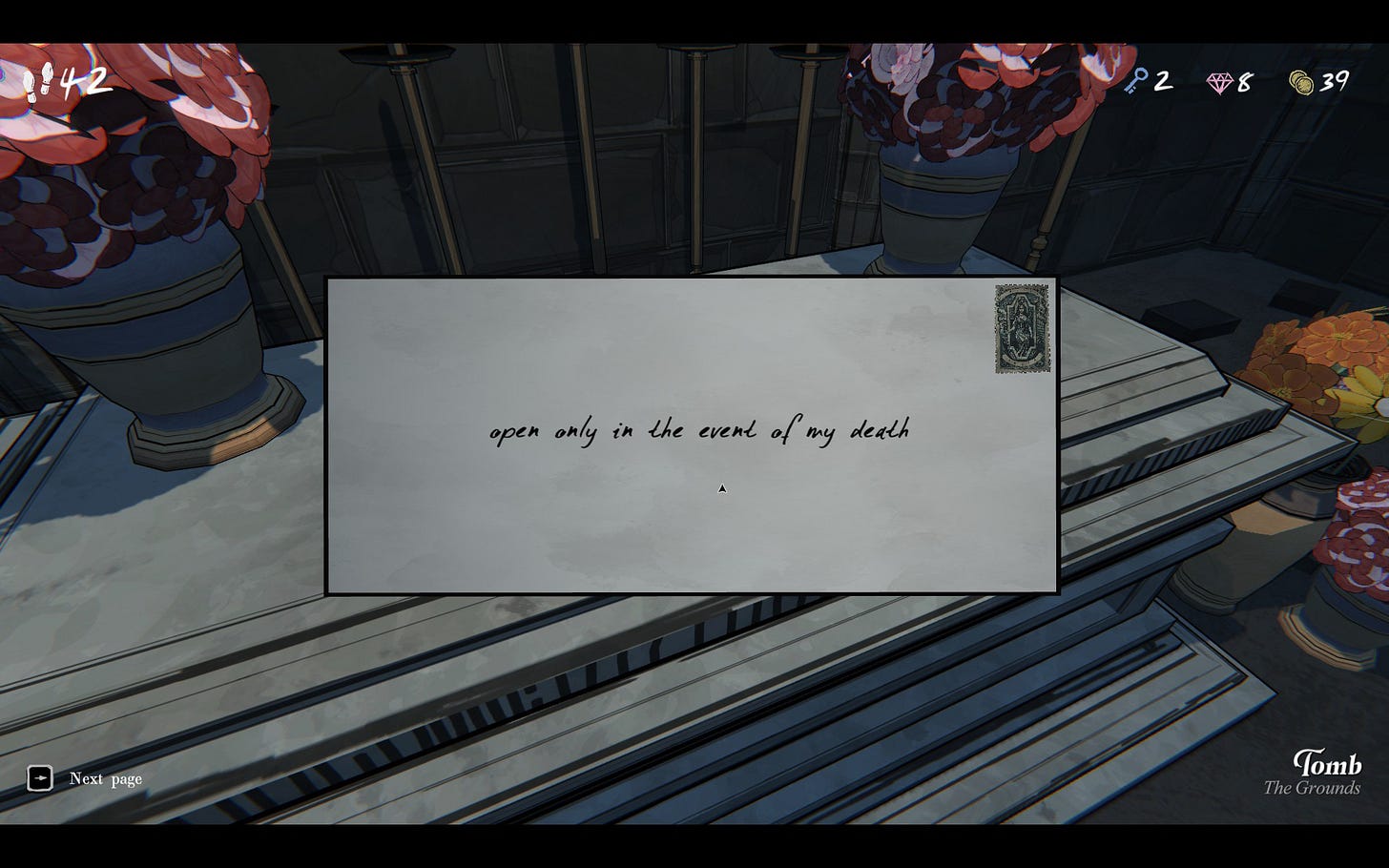

Blue Prince is a game where you are a young man exploring the mansion of your late uncle, whose will grants you the estate “on the condition that you can find the 46th room of the 45-room manor.” In the course of doing so, you’ll discover countless puzzles and slowly unravel mysteries ranging from family drama to workplace drama to high treason against the crown.

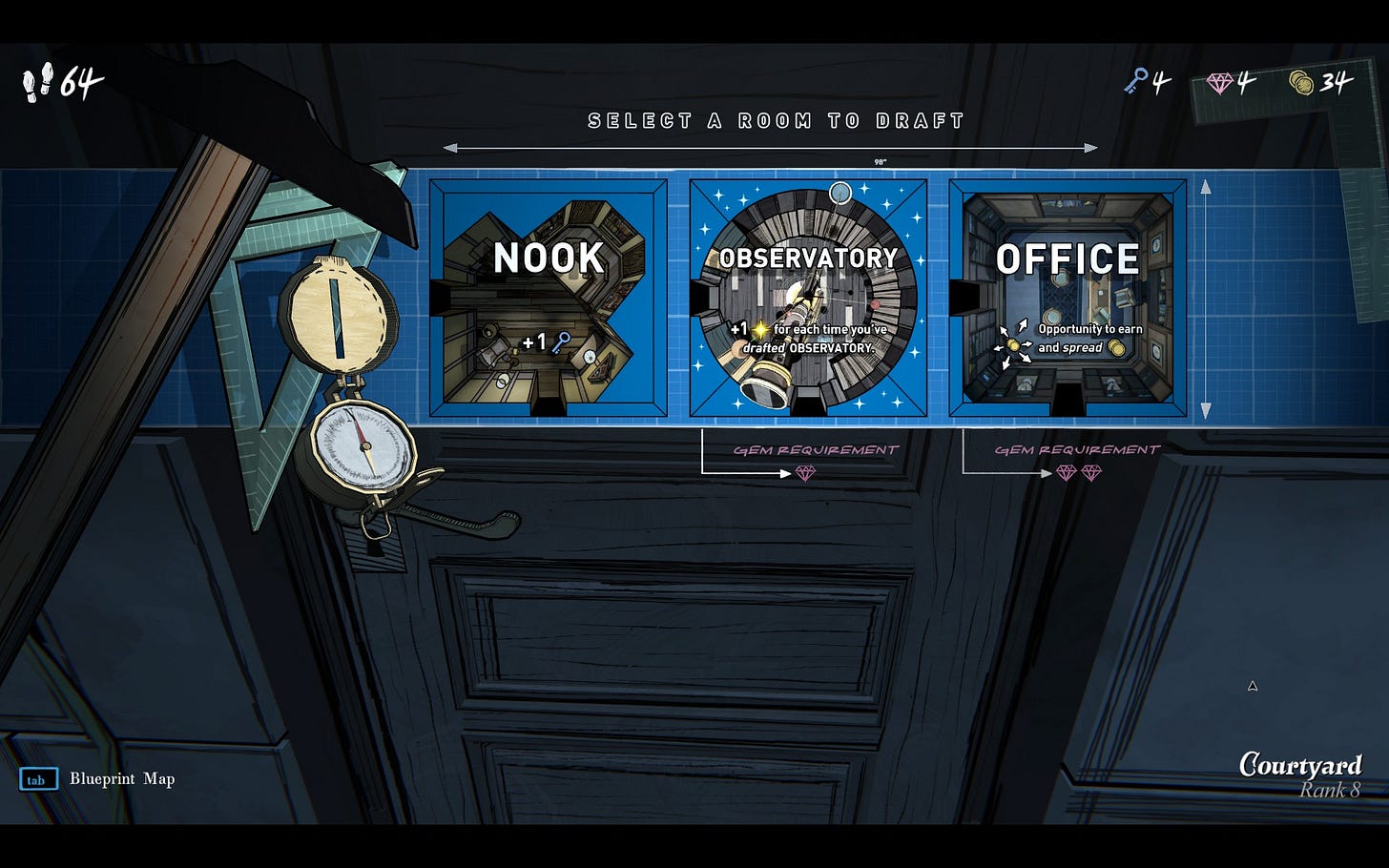

It has one major conceit, which is that the entire building shifts and rearranges every day, so as you explore each room on the floorplan, you “draft” what room will be waiting for you behind each door. When you can’t explore further in a day, you retire to a tent outside the manor and begin the house anew the next day. As with science fiction or fantasy shows, you cannot ask about the logic behind how this works, you must simply accept it, because that’s how the roguelike gameplay works. As such, it’s so accepted in the setting that there are popular architectural magazines about how to draft the rooms in your house well, suggesting legions of middle-class people in the suburbs whose bad luck or planning means they go days between being able to reach their own bathrooms.

Each day, you have a limited number of “steps” to spend going between rooms before you have to end the day. Rooms may contain food (giving more steps), keys (to unlock doors), gems (to draft certain rooms), and any number of other items and mysteries. Rooms have types, like bedrooms, hallways and green spaces, which adjust their themes, mechanics, and what might spawn in them day to day. You may find safes requiring codes to unlock. You may find letters or books or any manner of text talking about things in other rooms. You may discover that some of your items can be used in interesting ways in certain rooms. There’s not necessarily a mystery in every room, but it’s common enough that you’ll start to expect that there must be something, even if it’s not immediately apparent.

That sort of “superstitious play” is a powerful motivator of a mystery game like that. If you think anything might be part of a mystery, then suddenly you’re paying attention to everything. Even so, it’s not the most powerful psychological trick at work here — but I’ll get to that later.

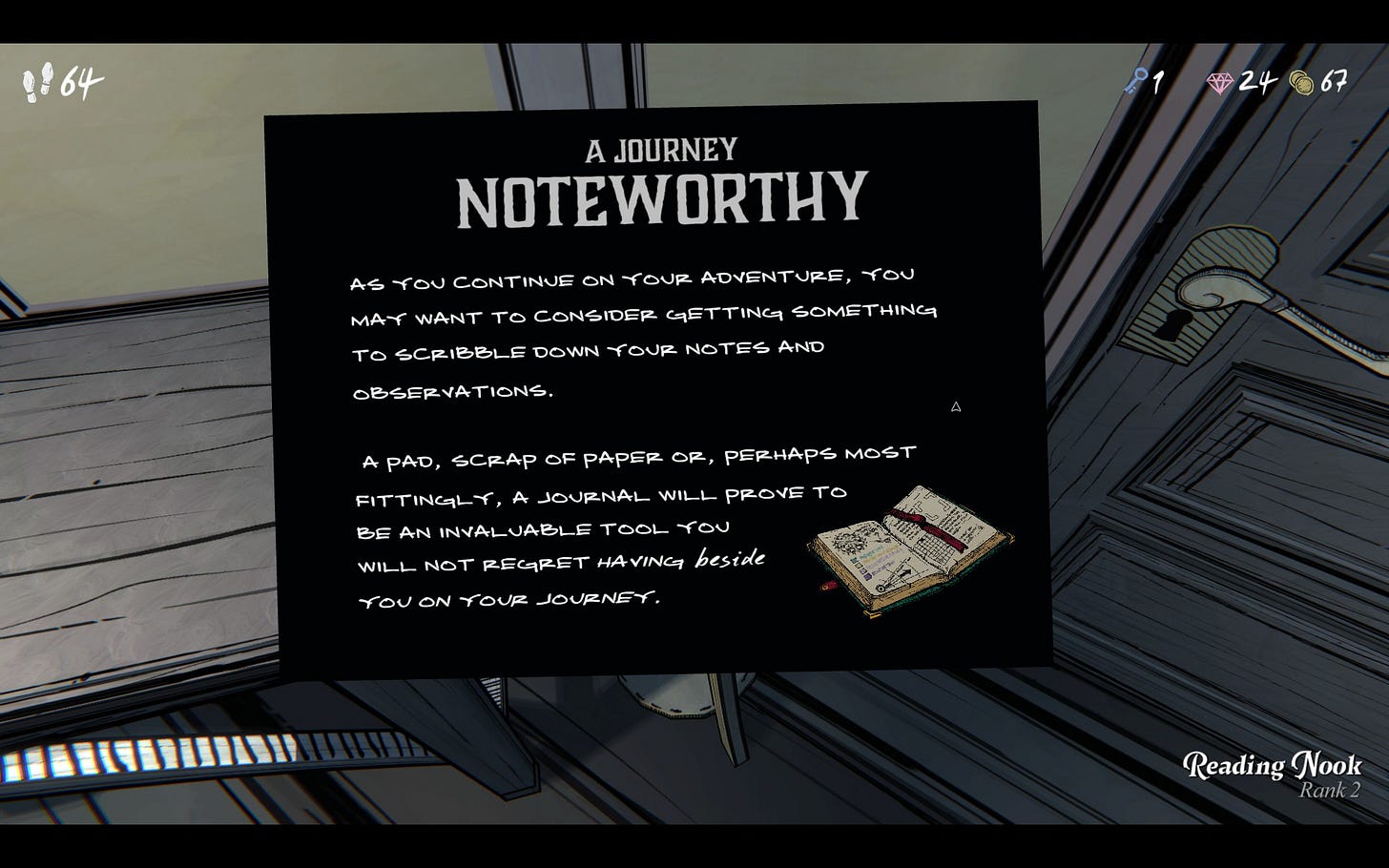

So, in the parlance of games, Blue Prince is Returnal meets Gone Home — a roguelike mystery game with lots of puzzles and even more contemplative walking around. The game explicitly tells you that you should keep notes on a piece of paper about the mysteries as you play. And there are lots of mysteries to ponder, along with multilayered stories to reconstruct and systems to figure out. Those notes are going to be important, because when you find a clue to something you’ve been wondering about, you can’t always and immediately go back somewhere and try to figure it out. Imagine playing Myst if you couldn’t control which parts of the island you were traveling to next.

Which, for a lot of game developers, goes directly against common wisdom in a big way.

Solving Puzzles and Delaying Gratification

In the long history of puzzle-gaming, from the early realms of Myst to countless point-and-click games, all the way back to text games like Zork, there’s been one piece of design experience that’s become such widely accepted common wisdom that it’s rarely even questioned:

“Once a player figures out the solution to a puzzle, executing that solution should be as quick and painless as possible.”

This has been received wisdom after generations of puzzle games that didn’t follow that rule, and that were deeply painful as a result. Figuring out a puzzle is the bit that releases the dopamine in your brain, and executing the solution is just getting the reward for doing so. Any delay between one and the other, and the experience loses its impact.

Blue Prince completely ignores that rule.

Because the layout of the house involves some degree of random chance — especially in the beginning hours, when you haven’t built up a bunch of permanent upgrades that make things easier — you may often find yourself in a situation where some clue or random inspiration tips your brain into figuring out a solution to a puzzle you’ve been thinking about… and then you just have to sit on that solution until the next time you get a chance to try executing it.

“Oh, this item I made says it “can light fires and ignite fuses”? I remember where I’ve seen a fuse! I bet I can use this to set off that dynamite!”

“… but not today, because I didn’t draw the room with that dynamite. Maybe I can try it tomorrow.”

By all common game design wisdom, this should drive players fucking nuts. And honestly, it does. At least, at first.

It really does come down to keeping notes. Specifically, it comes down to making a to-do list.

Remember that notice about keeping notes? It wasn’t kidding. To best enjoy this game, every time you find a puzzle you can’t solve, or a solution you can’t execute yet, or just a combination of room(s) and item(s) that you want to try experimenting with, add it to your to-do list. And then, as you explore the house every day, keep an eye on which of these mysteries you’ll have a chance to try on this run. No day will provide options for everything, but most days should give you a chance to address something on your list.

The result is a kind of magic trick on your brain. It’s not that you’re facing a single puzzle at a time, solving it, and then being frustrated as you wait for a chance to execute a solution — it’s that you’re facing a half-dozen puzzles all at once, being constantly distracted from solving one by discovering another, and then when the stars align again to let you try out a solution you’ve put together, the reward hits all the harder.

And that’s true even if the reward is, in fact, just clues for another mystery for your list that you’ll have to wait to try to solve.

The Downside

Of course, this only works if you have a robust list of items to pursue on each run. The moment you have a day or two where you feel like you didn’t make any lasting progress at all, the Frustration sets in.

The biggest threat for this is early in playing the game, , when you’re still figuring out what you can even do to pursue the first stated goal of reaching Room 46 (especially if, like me, you got the mistaken impression that you had to get there within one month of days). At this point, your real goal should just be “find new rooms you haven’t seen yet and check them out.” Room 46 can wait, I promise. Focus on finding new questions to explore.

Blue Prince does try to do a couple things to avoid leaving new players in this limbo. You’ll find that many of the early big mysteries in the game (like what’s up with the art in every room?) have multiple clues spread across multiple locations, all in the effort to tip players off to one of a couple of big puzzles early on, no matter what angle they’re approaching from. This can sometimes lead to redundancies, as you find a new source of information that just gives you a clue to something you’ve already solved. But for the most part, the game is pretty good about each piece of information giving multiple clues, to keep your to-do list full.

Even so, a mirror of that frustration can also set in as you approach the end of the (known) content, and your list of leads begins to get pretty thin. I’m at the point now where I don’t think I can make any progress on my to-do list unless I draw one of two specific rooms, leading to days where I can pretty quickly say, “Oh, don’t think I’m getting anything done today. All I can do is try to set up advantages for the next day.”

I already do that often enough in real life. Doing it in a game heralds the end of my time playing it.

Then again, if I’m getting to the end of playing a puzzle game after about 60 hours, 12 pages of notes, and over a thousand screenshots, then that means the game had a pretty successful run with me.

Yes, I’ll admit, Blue Prince had me hooked pretty hard. And looking back, it makes a lot of sense why it did.

The Psychology Behind the Gameplay

As with all good game design, there’s a psychological effect at play here, and it’s a powerful one: intermittent reinforcement. In short, if someone or something rewards you in an unpredictable fashion, you can find yourself striving against all reason to please it to get that sweet dopamine hit.

Intermittent reinforcement is strong but dangerous; the fentanyl of psychology. In more sinister contexts, this is the same psychological effect that makes lootboxes and slot machines so addictive, as well as a common trick used by pick-up artists and abusers. But in a context of a game that asks for nothing but your attention, this effect is far less sinister, if no less powerful.

And roguelikes are very effective machines for intermittent reinforcement, because each run can vary so wildly based on the random chances of getting an effective combination of elements. Or in the case of Blue Prince, getting a combination of rooms and items that let you discover a puzzle or execute a solution.

There’s even a brutal little bit of design in the moment after each run that reinforces this effect. When you call it a day, you get a quick little recap of the house you made, with a bit of info about new rooms or items you received. And then, you immediately have to make a choice: start a new day, or exit to the game’s title screen.

Most modern roguelike games would instead give you a cool-down moment between runes. Whether it’s Hades’ underworld, or Returnal’s crashed ship, many games with this sort of randomized runs give you a period between runs where you can review what you’ve unlocked, what you’ve already faced, and generally just have a breather to refresh yourself. And this is especially important in an action-heavy roguelike, where players just need a moment between fights — especially if they just ended a very exciting combat run.

But you don’t get anything of the kind in Blue Prince. You have to immediately start a new day (and you can’t save during a day, just end your run), or leave the game. If you want to explore your house, you need to do it during another run — complete with using up your limited steps. There’s no resting here, just play again or leave.

Epilogue

So, you’ve got a perplexing puzzle with so many hidden things that you quickly think anything might be part of a larger solution. You’ve got a multifaceted mystery that breaks game design wisdom by delaying “solving the puzzle” from “executing the solution”, but makes up for it by giving you lots of puzzles to pore over at once. And you’ve got a randomized roguelike design that uses intermittent reinforcement to keep you playing one-more-day to see which of your to-do list you can address tomorrow.

And what does that leave us with?

A lot of things, honestly. But at very least, a damned fine game that can draw you in and keep you hooked.

There are a couple of slight resonances with two other types of puzzles/games. First, a really well-designed crossword puzzle can toss you only a few easy answers, then lead you along with some "hints" in the form of partial letter-intersections and number-of-spaces guides. In the best cases, you will end up coming up with answers you never even knew. Second, the New York Times Spelling Bee has some puzzles that I have to step away from from time to time. Sometimes I even wake up with a couple of fresh solutions, and sometimes I wake up having misremembered an available letter. I think that the partial availability of solutions, coupled with the longer-term uncertainty, is the key to developing obsession (a less scary word for addiction these days) in the player.

Thanks for write-up. Game resonates for me with Outer Wilds where each run I would crack a little bit of the wider puzzle and better understand the world. Similarly feeling of the leads getting thin at the end as I accumulate knowledge but it seems the major delta is the lack of randomness lets you drive to a thrilling conclusion with certainty in case of OW.