Emergent Narratives: Finding Ghosts in the Machine

Finding the stories that show up between the rules

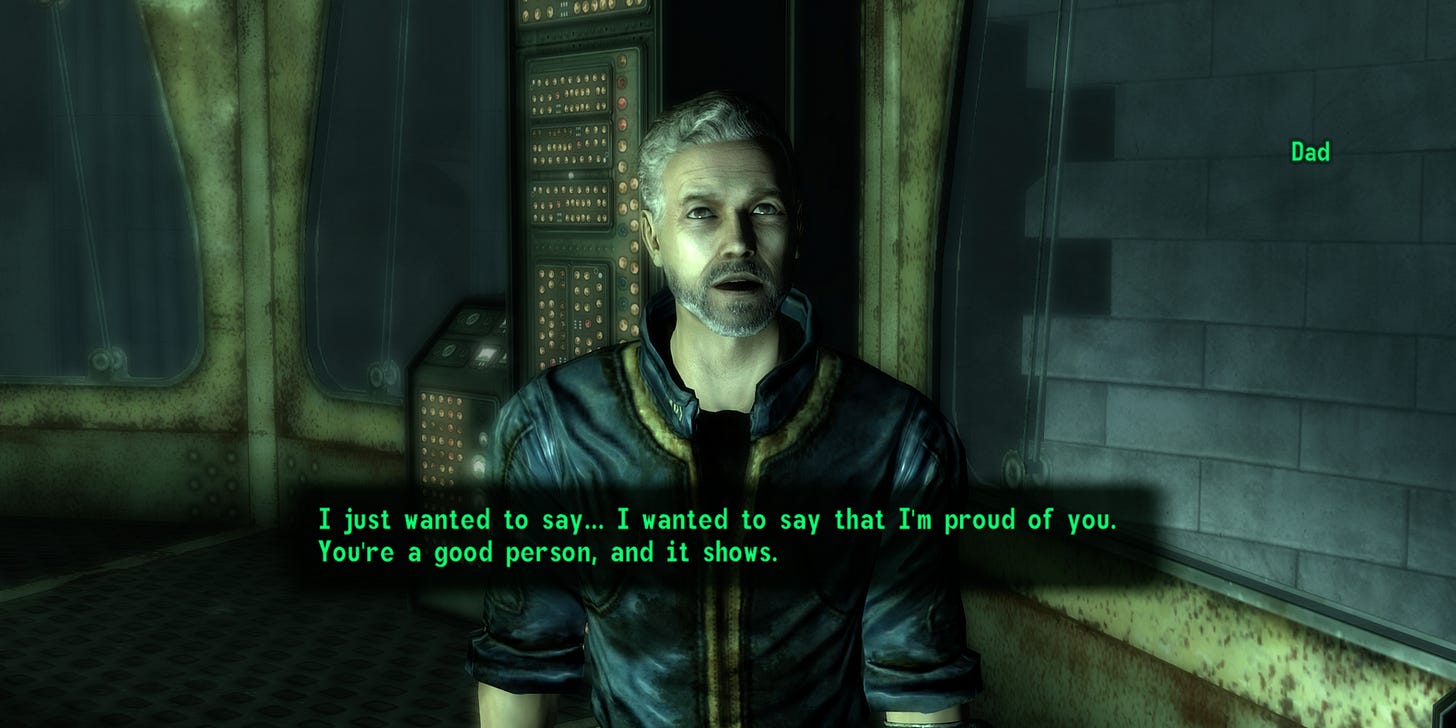

Towards the end of development on Fallout 3, there was a moment of pure alchemy and bloody violence that made it clear to me we had made something wonderful. It was a piece of emergent narrative that shook my entire relationship with one of the key characters, and completely changed how I thought about them.

And ever since, I’ve been thinking about what goes into making that kind of emergent narrative experience, both from a game designer setting the stage for it, and from a player looking to find it.

This was shortly before lock on development, when most of the game is done and designers have little we can do except playtest and fix the most egregious bugs. I had played most of the quests in the game before, in isolated bits and pieces, but this was one of my first times playing “naturally” from start to end with the fresh eyes of a new player.

I had decided to focus on the main questline, and had just found and rescued my character’s father, who had recently abandoned him in Vault 101 to return to the Wasteland. And I had decided that we’d make the long trip to Rivet City together on foot, without any fast travel. In part, I wanted to spend some time with him again. Also, we had just gotten Liam Neeson’s lines recorded, and I wanted to hear the fully-voiced Dad.

Along the way, we came across a fairly standard random encounter, and as you might expect from a Bethesda game, the encounter immediately descended into violent chaos.

Short version: Dad committed some murder and I ended up covered in guts and disillusionment. But we’ll get to that later.

To fully appreciate this example of emergent narrative, I want to first explore the two things that had to come together for it to work: the way the game’s rules were designed with interlocking systems, and the way the player has to be actively looking for a story.

Designing the Rules and Letting them Run

When you’re making any interactive fiction, you’re going to give up some of your direct authorial control. You won’t be controlling the pacing or exact details of your scenes, but you still control the rules.

This means you control the broad strokes of how things can play out, and in gameplay that sets a tone very much like you would when writing a scene. If your NPCs behaviors tend towards being greedy and violent, that’s what will come up more often. If combat escalates quickly and horribly, you’ll see that more likely than not, too. If resources are scarce in your loot tables and always desperately needed, players will feel that hunger in a way that can feel even more personal than just reading about it in words on a page.

What’s more, you want to have systems that can interplay with each other. Say, a hunger meter for your NPCs that runs low (because food is scarce) and changes their behavior to be more violent in seeking out food — it’s a simple example, but the more your systems can influence each other, the more you’ll see these sorts of chain reactions that can lead to unexpected moments. And so, over the course of a few hours of play (or a dozen, or a hundred!), you’ll see these sorts of unexpected situations emerge time and time again.

Bethesda games are pretty good for this largely because of their robust behavior AI system for NPCs, handling situational behavior, needs, factions, combat behavior, and more. It’s kind of a ramshackle engine that has been pieced together over decades of games, and it produces at least as many amusingly broken behaviors as it makes beautiful moments. But for someone looking for these moments, Bethesda games provide ample material.

Meanwhile, the undisputed king of this sort of thing is Dwarf Fortress — a “colony simulation” so detailed that it models dozens of traits across scores of characters in a base that’s always facing shortages of materials and unexpected challenges. It, and similar games like Oxygen Not Included or Rimworld, have countless layered and interacting simulations running. And as a result, they also lead to fascinating moments of unpredictable behavior — but the combination of their presentation styles and the tone of their underlying rules can lead to emergent stories that feel very different from each other.

The System at Work

Now, that we know how interlocking systems can prompt unexpected behavior, let’s take a look at how they worked in my Fallout 3 encounter.

From a pure scripting and gameplay point of view, this is what happened in the course of maybe a minute of gameplay:

Walking along the Wasteland, we run into a random encounter: two raiders attacking a traveling trader and his brahmin.

Dad has raiders as an opposing faction, so he immediately charges into combat against them. Not having any weapons at the moment, he charges in bare-handed.

I know Dad’s a vital NPC, meaning he can’t be permanently killed, but I want to help him out, so I go into VATS and kill the raider closest to him, hoping to keep him more or less safe.

Dad’s AI immediately recognizes that there’s now a nearby weapon with a higher DPS, so he grabs and equips the dead raider’s automatic rifle and starts spraying the other raider.

In the process of the shooting, he or I must have accidentally clipped the trader who was nearby, which means the neutral trader now sees us as an enemy faction as well.

Dad and I continue to shoot the remaining raider until he’s dead. But the trader has also aggroed on us now, so Dad proceeds to shoot the trader to death, as well.

I briefly assume that’s the end of it, until I’m headbutted by the trader’s brahmin — because it shares the same faction affinity as the trader it was with.

Dad’s AI is still in combat with the aggressive brahmin, and now that the trader is dead, he recognizes that there’s a new weapon nearby with an even higher DPS — a rocket launcher that was in the trader’s sellable inventory, lootable now that he’s dead.

Dad picks up the rocket launcher and immediately fires a rocket into the brahmin that’s in melee range of me, catching me in the blast and exploding the poor beast into giblets.

Dad’s AI recognizes that combat is now over, and says a “combat completed” bark as he returns to his normal non-combat AI of walking next to me.

Looking at it with the eyes of a designer and tester, I know that these are the cogs that are turning inside the machine that worked properly to create this moment. The tester in me says “yes, all functioning correctly, carry on.”

But the player in me has to take a moment, because considering the whole experience in the context of the rest of the game’s story has me reeling.

Looking for a Story Among the Rules

Not every player is playing a game for the story, and that’s fine. Not everyone is watching a movie for the cinematography, or listening to an album for the percussion. Those are still important parts of their media, but as far as these audiences are concerned, they’re just happy if those things don’t get in the way of what they’re there to enjoy.

But players who are playing for stories need to meet games halfway. This may sound like an inditement of games, but it’s true for pretty much every storytelling medium — we’re just culturally used to the ways we meet books and movies and TV shows halfway. There’s a media literacy that people pick up for each format — “people in TV and movies only have truncated phone calls”, for example — that would seem baffling to audiences of other eras. But those who are familiar with their modern formats just mentally smooth out the unrealistic parts, fill in the gaps, and elaborate from storytelling shorthand to form the story they remember after the media is over.

Video games are no different in that regard. Players who care about stories have been reading emotions into characters a dozen pixels tall and discerning personalities from simple follow-scripts for decades now. So reading emotions into complex systemic behavior is hardly a stretch.

The ideal player for finding emergent narrative is one who’s not only interested in finding stories, but invested in the characters enough to explain to come up with motivations to explain their behavior beyond the simple behavior of their scripting. Knowing the themes of the setting lets them use that context to imagine an inner life to the NPCs that justifies their actions.

They also need to be able to look close enough to follow an individual character and see their behavior in that world. A first-person perspective can help with that, but it’s far from necessary — even a top-down, abstracted view can still give an invested player enough insight to what’s happening to fill in the gaps for those stories.

![Video Games/Dwarf Fortress] The sad story of Boatmurdered, a tale of death, insanity, administrative failure, rampaging Elephants, burning puppies, and cheese. : r/HobbyDrama Video Games/Dwarf Fortress] The sad story of Boatmurdered, a tale of death, insanity, administrative failure, rampaging Elephants, burning puppies, and cheese. : r/HobbyDrama](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!4csc!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fb3d8acd0-901e-4957-9545-752668035ea9_350x438.png)

The Story Emerging from the System

Back to my Fallout 3 experience: a random encounter with Dad has gone badly awry. On a system level, everything has played out normally. But as a player who’s invested in this story and understanding why my I was abandoned in the Vault by my wayward father, my experience is this:

I’ve left the safety of everything I knew in the Vault to find my Dad and understand why he left me behind. After rescuing him, I’ve taken the opportunity to walk with him and see the world he left me to return to. And the first encounter we had together with other people has turned into an absolute bloodbath.

Within an hour of my reunion with Dad — the kindly father who spent my childhood talking about waters of life and mercy and justice — he has just murdered three people in cold blood, including a man he was supposedly trying to save. Then he blew up an innocent, confused animal with an anti-tank weapon, burning his son and coating him in bloody gore.

And what did he have to say about it?

“I’m sorry you had to see that, son.” he said, in the sort of sad-warm-menacing voice that Liam Neeson would eventually deploy in the Taken movies.

Good lord, Dad.

Suddenly I realize that this is the sort of horrible good-deed-turned-bloody-murder that you know happens out here in the Wasteland. You’ve only been back out here for a few days, and you’ve already become a monster. Maybe you always were one.

Now I know why you didn’t want me to leave the Vault in the first place.

Sometimes, all of a game’s complex mechanics can come together just right to make something beautiful. Or horrible. And there are ways you can design for that.

But you also need a player who’s willing to look for it, as well.

It's a good thing it was your Dad, and not your Mom: "Mama Bear Mode" is even worse.