Every Layoff is a Personal Tragedy

In a year full of studio closures and mass layoffs, it's easy to forget the human scale

Recently, my friend and colleague Alexander Newcombe was one of the over 22,000 gamedevs to suffer from the wave of industry layoffs that we’ve seen since 2023. His studio, Phoenix Labs, had closed and ended development on their unreleased game Everhaven.

Being a narrative designer like me, he processed the experience in the way we know best: writing.

Specifically, Alexander wrote about the heartbreak of telling his kids that the game he had been working on — and that they had been helping playtest — was suddenly gone. It’s a beautiful and moving look at just one of the many tragedies that each layoff represents. I highly recommend that you read his piece at Patrick Klepek’s substack now.

A Familiar Heartbreak

It seems like any dev who’s worked in games for a while has gone through similar heartbreak. And each time, there’s little you can do except write a little eulogy for the future you thought you were going to have and then try to move on. Or, as is increasingly common right now, you leave the game industry completely — honestly, I can’t blame anyone who does, these days.

Layoffs can uproot your entire plan for the future. Looking for a new job in the game industry is a process that often takes 6-12 months, especially as you reach more senior levels, and even in this day of remote work it can often require relocating to a new city or country. Finding a way to pay your bills during that time can mean living off savings (if you’re lucky enough to have them), unemployment, or finding whatever side work you can.

Some people might claim it gets easier, but what it can actually do is make it harder for you to trust in any sort of long-term existence in game development — a sort of complex PTSD that can undermine countless other parts of your life. If you can’t trust that you’ll still be in a city three years down the road, it’s hard to bring yourself to do things like buy property or build long-term connections.

It’s no surprise then that the National Board of Economic Research found that layoffs lead to increased mortality rates, equating to a loss of 1.5 years of life expectancy for each layoff a person suffers in their career.

Personal Cost

Personally, I’ve been through two studio closures and two mass layoffs over my career. It’s one thing to have willing spent eighteen years in the art of making games — I’m happy to keep exploring this craft for my entire life. But to consider that I’ve statistically lost six years of that life due to layoffs from the industry/business side of it is especially bleak.

Getting gamers and wider audiences to understand that human cost behind every layoff is one of the reasons why I started this substack. Hell, writing to process that tragedy is what led to my first published piece of writing about games at all, even though it was done anonymously at the time.

But in the vein of Alexander’s article, I’d like to share my own tale of my first layoff from about 12 years ago. This was first published in a Kotaku piece by Jason Schreier, a journalist who’s interviewed me about two different studio closures for his book Press Reset: Ruin and Recovery in the Video Game Industry.

The tale is repeated here without permission, but also not for profit. I’ve added some links, images, and the occasion update from the decade-plus, but mostly left it intact.

Big Huge Games

When people talk about Curt Schilling and the 38 Studios closure, they tend to forget that it also killed Big Huge Games as well. They had bought BHG a few years earlier, and under them we had had just released Kingdoms of Amalur: Reckoning.

We were proud of the sleeper hit we had made against all odds, and we were very focused on what we had to improve for the next game. EA had done some restructuring, resulting in dropping our plans for a sequel, but this was an amenable break — they let us keep all the rights, and we had other publishers who were interested in picking us up for Reckoning 2. It was a bit of a shift, but we weren’t too worried.

So we continued working on pre-production and the re-balancing patch while management found a new publisher to work with us. A couple studios were drawing up offers.

Things were going so well that as the release date for Diablo III approached, the studio declared that we’d have a “research day” — all employees would be encouraged to come into the office and “research other work in the industry.” This sort of thing happens at lots of studios during major industry releases. After all, it’s a better solution than having everyone call in sick to play at home.

It was a Tuesday, so we met for our regular Tuesday morning meeting, with breakfast catered by the deli in our building. As we were all chatting over eggs and muffins, one of my coworkers mentioned that something must be wrong with his bank, because his paycheck hadn’t gone through to his account. Another coworker said she was having the same problem, but with a different bank. Instantly, everyone was on their phones and checking their bank balance. None of us had been paid.

We immediately knew there was a problem, but we didn’t realise how big it was. When our meeting turned into an impromptu phone call to payroll at 38 Studios, they assured us that it was just a minor error and that we’d all be getting our checks immediately, once they straightened things out with their bank. Go ahead and play, we’ll have it solved and let you know at the end of the day. Curt Schilling apologized for the mistake and promised to make it up to us all.

“Start looking for a new job.” my friend said, “Right now.” But I was sure it was just a temporary mistake.

We played games, made jokes, then reunited for the end of day meeting. 38 Studios was having an all-company meeting to explain what had gone wrong, so we all piled in to join via webcam. There had been a clerical error, Curt said, and it was being fixed. Our paychecks were all printed and ready, but the bank had to fix one more thing before they could be delivered and cashed, they said. It’d be ready first thing tomorrow morning. People asked polite questions about how to avoid this in the future, or made jokes about getting time off until this was fixed.

We met again the next morning, a little less enthusiastic. There were still inconsistencies, they said. They’d have it all worked out by the evening meeting, they said. At the evening meeting, they had more excuses, but promised the paychecks would be coming the next morning. The questions got a little less polite and the jokes got a little more barbed.

This happened every day that week. Curt started tearing up when he apologized to us. Then he started getting defensive and angry when he was asked questions. Eventually, he stopped talking to us at all.

We kept coming in because our team was very close, and many of us didn’t have anything else to do during the day. Few of us were getting work done, although even fewer of us had started looking for new jobs. The balancing patch had to be put on hold; it costs money to release an update to a game, and we didn’t have that. We were all sure it’d be worked out eventually.

Most of all, we were looking at what we could do to make Reckoning 2 more attractive to potential publishers. We knew that as long as we had a publisher for the sequel, we could survive, even if 38 Studios collapsed.

On Friday, BHG officially let our in-house QA department go. It was the first time we had admitted that this wasn’t going to get better, and it hit us hard because these were our friends who had worked alongside us for years.

Once we had a publisher, we’d hire them all back, we promised. It’d be ok, we said. We drank with them at our desks through the day. At the end of the day, 38 Studios told us that everyone was officially on furlough until they worked things out.

That weekend was rough. None of us had been paid, and those of us who lived paycheck to paycheck were getting pretty lean, but we were hearing horror stories from up in 38 Studios that put our troubles in perspective.

You’ve seen the reports, I’m sure: mortgages in foreclosure, pregnant women learning they had lost their health insurance at the doctor’s office because 38 had stopped paying it, all that sort of thing. We even learned that management had stopped paying the deli for our Tuesday breakfast meetings, running up a tab of thousands because the deli owner had known and trusted us for years. We didn’t know how to break it to him.

The next week, most of us came into work anyway. No one had shut the office and we’d spent so long together crunching for Reckoning that it was our second home — plus, most of us didn’t want to be on our own. The news out of 38 was getting more and more dire, and we were realising that they wouldn’t be coming back, so we turned all of our efforts towards getting another publisher to pick up Reckoning 2. Our official layoff emails came from 38 Studios and we barely noticed them as we prepared for visits from interested publishers. It may have been too late for 38, but Big Huge Games could survive.

Then the governor of Rhode Island started making 38’s collapse into a political issue and it became mainstream news. Politicians and bank officials quoted scary-sounding numbers about our finances out of context, and they were repeated around the world by news sources who knew nothing about the process of making games. “Amalur” became synonymous with mismanagement. The publishers who had been talking with us decided the whole situation was toxic and pulled out of talks with us.

We couldn’t blame them. We knew it was all over.

Usually, when a studio closes, a handful of people are kept employed for a while to ensure that shutdown goes smoothly: offices are closed, assets are cataloged, legal issues are settled, etc. But this closure was entirely unplanned, and we had none of that. For a week, it was chaos.

We still hadn’t been paid, and the government and the bank had first priority of getting repaid from the money that 38 no longer had, so we knew we’d never be seeing our last paychecks. People started packing up their things, saving copies of work for their portfolios, grabbing mementos from around the office. Everyone was sharing news of job offers and advice about how to sign up for unemployment. Other studios were sending people for an impromptu jobs fair at the restaurant nearby.

Some of us found jobs. Some of us quietly turned our backs on the industry forever. The drinks we had kept for special occasions were drained in countless teary-eyed toasts.

We knew that the studio’s official assets would be put up for auction (not that we’d see any of the money), but we also knew that the only assets that could be officially tracked were the things IT had tagged. Some might have called it looting, but since we were all owed thousands of dollars apiece, it seemed perfectly reasonable. Computers and monitors stayed, but everything else was fair game. The high-quality marketing toys like replica weapons and standees were divided up between our coworkers as consolation prizes for how hard they had worked. Ex-coworkers came into the office for a proper farewell. We had a mini-reunion at work. Then at the bar. Then wherever we could gather. We still do, whenever we run into each other at GDC or the like.

Eventually, we knew we had to leave the office. An outside company would be coming to catalogue its assets and move everything into storage. So we packed up the last of what we could salvage and turned out the lights as we all went our different ways.

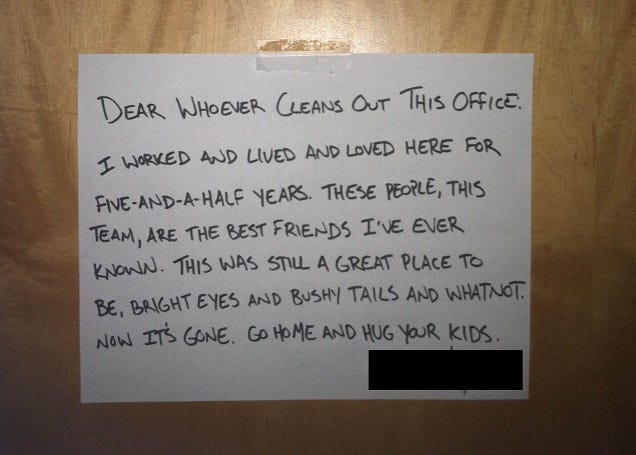

One coworker — the nicest, sweetest human I’ve ever worked with — left a note on his office door for the movers:

A month later, Game Developer magazine would name us one of their top 30 upcoming developers… with a last-minute editor’s note.

And that’s how our studio closed.

Go home and hug your kids.

(POSTSCRIPT EPILOGUE: While many of us from Big Huge Games went on to other studios, I’m happy to say that the studio itself was reformed a few years later by many excellent survivors, and now successfully develops the mobile game DomiNations. The fallout of the 38 Studios collapse was extensive and well-investigated. However, even after a nearly decade-long civil suit, few of us have received the back-pay that we were owed, and even then only cents on the dollar. We still meet and share drinks when we can at GDC and elsewhere.)

It was about 3 weeks before it all crashed down at 38 and I had a downpayment check out to the realtors on a new home in Rhode Island. Something just felt off to me - no idea what or why because there weren't any signs of trouble yet. So I called my realtor and asked for the check back, and we met at a closed gas station between Mass and Rhode Island so she could give it to me. We 100% would have gone straight into bankruptcy (like others did) if we had gone through with buying that home once the company collapsed. What a wild ride.

I got my first "regular" job in 1977. The company was sold in 1979, but I was able to continue, although my actual work duties changed. Not everyone was so fortunate. I survived a relocation and some other restructurings until a big reorganization in 1992. I survived doing freelance work before landing full-time at Fox News Service in January 1993. Six months later, Rupert Murdock shut down our entire operation. I landed in a high-tech govenment contracting company in 1996, but that got sold in 2001 to a company that in turn got sold a couple of years later. I met one of the former Vice Presidents of that company around 2016, when he had become a Blues musician. After that, I was at a splendid company until I became disabled, but even they got sold. At interview time, the HR person used to ask "where do you see yourself in five years?" Now, nobody knows where they will be in five years.