Fantasies: the Power Fantasy

The hyper-competent hero we wanna be... depending on who "we" is.

About a decade ago, I was working at a studio I won’t name. On my first day, they told me they had cancelled the project I had been hired for, and my new job with the other writers was to pitch concepts for their next game’s setting, story, and characters.

On the one hand, this was exciting — the potential to create a major new franchise from scratch, and see it through to full creation is always a dream. But it quickly became a nightmare, as it became clear that no pitch would be accepted unless it met the convoluted and mutually-exclusive requirements of all five directors and two founders for a unanimous agreement.

Spoiler: over the course of six months, they never agreed on a single pitch, and my notebook full of new IP pitches was filed away for future use.

One of their many requirements was that it had to “be like The Last of Us”, which had been a huge hit recently. So with that cue, one of my pitches involved a tale of a father and daughter who had become separated by war and fate, with the player alternately playing each one in different chapters, utilizing different skill sets and fighting different threats as they sought to be reunited.

Like every other pitch, it was rejected. I can’t remember exactly which of the panel of guys said it, but I’ll never forget the reason given for its rejection:

“Here at [STUDIO NAME REDACTED], we design our characters to be aspirational,” he said, “and our players don’t aspire to be girls.”

Needless to say, I wasn’t pleased by this response. When they gave up thinking of a new IP and laid off the entire writing staff a few months later (on the Monday after the Christmas party), I was neither surprised nor particularly saddened to be done with the entire studio.

Now, I survived being laid off, and the studio went on to be told by their publisher what their new IP would be, since by that point they had wasted a year and a half with nothing to show for it. Time moved on.

But I never forgot the importance studios place on aspirational characters. Nor the shitty assumptions some people have about who can and can’t be aspirational.

Someone Players Aspire To Be

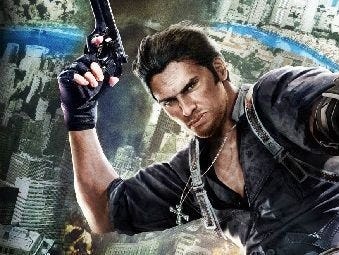

It’s true that most games strive to give the player an aspirational, iconic character. In action games in particular, they aim to present the player with a Power Fantasy — someone exceptionally capable and competent in their world, who the player can embody as they war with gods, raid tombs, or triumph over whatever exceptional threats that exist in its setting.

In most cases, this is someone exceptionally powerful and tough, but it really depends on the challenges in the game. Batman is a classic example: a brooding paragon who is both unsurpassed at martial prowess while also being the world’s greatest detective and having all the coolest gadgets that money can buy. And he’s perfect for the Arkham Asylum games, which will require both stealth, combat, and gadget-based detection.

But other sorts of games may offer different definitions of “power” — the smooth and stylish world of Jet Set Radio may offer unnaturally sleek and agile skater punks, while the a series like Metroid presents a highly versatile and adaptable bounty hunter. Whatever the setting, the Power Fantasy is uniquely well-suited for handling its threats, and the player just has to develop the skill to deploy their specific talents and feel like the character’s victories are their own.

Now, you will have noticed — clever and insightful reader that you are — that none of these character traits are inherently gendered. Certainly, traits like “strength” and “violence” are culturally associated with masculinity, but are hardly unique to men (just as “agile” and “quick-witted” are not unique to women). There is nothing to prevent your Power Fantasy archetype from being either gender (or non-binary or non-gendered). Alas, there are some bad-faith actors who may read a physically-dominant woman as being masculine, but these are bad-faith actors who will take any opportunity to complain about women being protagonists in games, and their fringe opinions should be broadly dismissed as the politically-driven agenda that it is.

Besides, in a world full of action games starring similar brown-haired white grumpy guys, anything you can do to make your character stand out from the competition is a plus.

Regardless, the average Power Fantasy character demands a design that your players are able to embrace and identify with, especially considering that the player will be embodying them for dozens to hundreds of hours. If your design focuses on the character’s hyper-competence in the game’s focus, you can generally rely that a person drawn to playing that sort of game will want to identify as someone who embodies traits related to that game.

But not every sort of game demands a hero who looks hyper-competent!

When to Avoid the Power Fantasy

In fact, in many games, a Power Fantasy type of character design would be actively counterproductive to the experience.

Horror games, for example, rely on the player feeling threatened and outmatched by the dread creatures stalking the player — nothing would kill that experience quite like a character who looks like they could take out the serial killer with their bare hands. Although the exact sort of horror experience still makes a difference.

For example, compare Resident Evil vs Limbo. Both are horror games, but the Resident Evil games see you fighting the horrors, so their characters ultimately embodies the power fantasy. In games like Limbo, on the other hand, the player is largely fleeing from horrors, and as such should appear as powerless as possible. And their lead character design couldn’t make that distinction more clear.

Similarly, there are countless games that thrive on an unlikely-looking hero who triumphs over superior challenges. Certainly, this has been more common in game genres that focus less on action than on puzzles. And games with humorous or rebellious tones also benefit more from the contrast of “the triumphant loser” in character design. Both of these factors are were common in the golden era of point-and-click adventure games.

But you can also play a long game with a Power Fantasy design, where you begin with a character who seems weak or normal, but who grows into their power over the course of a game. This can be more costly in terms of art and design, as it involves developing multiple looks for the main character over different stages of their journey. But the results can be excellent if done right — and by the time you’re done with their first game, you’ve got a power-fantasy design that’s ready for the sequels — and that players feel like they helped build in the previous games.

Know Your Fantasy

Ultimately, designing your game’s protagonist means knowing what sort of fantasy you’re encouraging in your player. Oftentimes, it’s the escapist fantasy of being hyper competent in a dangerous world, in whatever way that’s measured. But sometimes you’re promising a different sort of fantasy — overcoming the odds, growing and exceeding expectations, or just being a character who promises an amusing time. Anyone can find themselves drawn to embodying these fantasies.

Then again, sometimes these games tempt players with a different sort of fantasy. Next week, we’ll take a look at what that’s historically meant in games, and what it could mean in the future of gaming.

It might be interesting to see a protagonist who was a hybrid between Harry Langdon (the seemingly ineffectual silent comic), Mona Lisa (able to assume the appearance of a print of a paintiing for the ultimate conspicuous-but-ignored disguise), and a variant of "Thing" (the disembodied hand from the Addams Family, with some added equipment like a portable eye for surveillance). The protagonist would be surrounded by witless muscle-bound types in revealing clothing and armor that just gets in their way (they would not be the antagonists, just some hapless wannabes who get into trouble). The hybrid protagonist would have to save them from things like powerful magnets (which would trap them in their armor) and blue-lipped censors (who would drop heavy sticky cloaks over not only their outfits, but also their faces, blinding them...of course, a blast of extremely cold weather might also have a chilling effect). Another antagonist might be an overly affectionate monster or person who just smelled really bad.