Game Writing Conundrums: Dialogue and the Uncanny Valley

Engaging the player's imagination, and when adding more gives you less

Back around the turn of the century, the big debate in games was whether a video game could make you cry. Sony pushed it with their advertising for the PS2’s “Emotion Engine”, doubled down on it with creepy PS3 ads a few years later, and a new generation of hardware that could handle better facial animation made promises of new levels of connection with players.

I already knew my answer, because I had grown up playing Infocom games. In particular, I remembered one lonely summer at the age of 11 when my family moved to the countryside and I didn’t know anyone, where I had gone back and replayed some of my favorite of those old text adventures. And among them, my time with Floyd the endearingly useless robot in Stationfall (written and designed by the legendary Steve Meretzky) had absolutely moved me to tears.

Without going into spoilers for a game that’s been out for 35 years, I’ll just say that simple text descriptions of the charmingly ineffective Floyd the Robot painted the image of an endearing, childlike sidekick in exactly the way that modern games like Bioshock Infinite or Zelda: Ocarina of Time would spend millions of dollars failing to do with their NPC companions. This was all the more impressive because the text-only adventure never actually describes what Floyd looks like.

But I noticed something interesting as I grew up and games became more graphically rich experiences. It really seemed like the quality of the writing itself fell — even when it was still the same author telling the story. Despite the addition of pictures, animation, and even full-motion video, I found the stories in many games less less and less engaging — even when they were written by the same person.

Now, some of this was surely nostalgia — few pieces of media ever feel as good as the media you loved in your hormonally-charged teenage years, and many a fine artist has been distracted by trying to recreate the experience of that lost youth.

But it’s not all nostalgia: there really was an era when we went from being excited about the quality of writing in games to broad dismissal of game writing as a whole. And it’s not a coincidence that it coincided with the chase of increased realism in games.

Dialogue and the Realization Triangle

Over the years, writing for games has largely come to mean “dialogue for characters", with occasional snippets of prose for in-world books and item descriptions. As text adventures were replaced by visual ones, descriptive text has been relegated to smaller and smaller details that are either too fine to notice in gameplay or too expensive to render in full.

So whether it’s sprawling conversations with a major character, orders delivered by commanders and questgivers, or the barks of soldiers reloading on a battlefield, most of what a game writer puts on paper is going to be spoken by a character on the screen.

In text-based games, dialogue was purely about the words, with the details of its delivery conveyed largely through how the reader cares to interpret it. When Floyd the Robot responds to the player saving their game by saying “Oh boy! Are we gonna try something dangerous now?”, you have a lot of artistic license to imagine exactly how he looks and sounds.

Today, NPC dialogue is almost always fully-voiced and delivered by a speaker we can see. In most cases, there are three major components that go into the realization of dialogue in modern games:

Writing Quality — the actual words themselves, their content and subtext

Audio Performance — the vocal work of the speaker, what they choose to stress and imply both in the words and in the character speaking

Visual Performance — the physical performance accompanying what’s said, from the speaker’s body gestures and facial expressions to the reactions of listeners around them

And the thing is: if any of these elements are clumsy or don’t work for whatever reason, then the whole experience feels bad. But if any of these elements are completely absent, the player’s imagination fills them in.

It takes a keen-eyed editor or a savvy critic to be able to identify when one piece of this triangle is dragging the others down — when a lackluster delivery kills a good line, or when a character’s static animation undercuts a vibrant delivery. Most people who aren’t professional writers, performers, or critics will simply say, “this writing is bad.”

Humans are wired to look for a tremendous number of subtle details in face-to-face conversations, so when any of those details are off, the whole experience sinks into the uncanny valley.

The Uncanny Valley and Audience Imagination

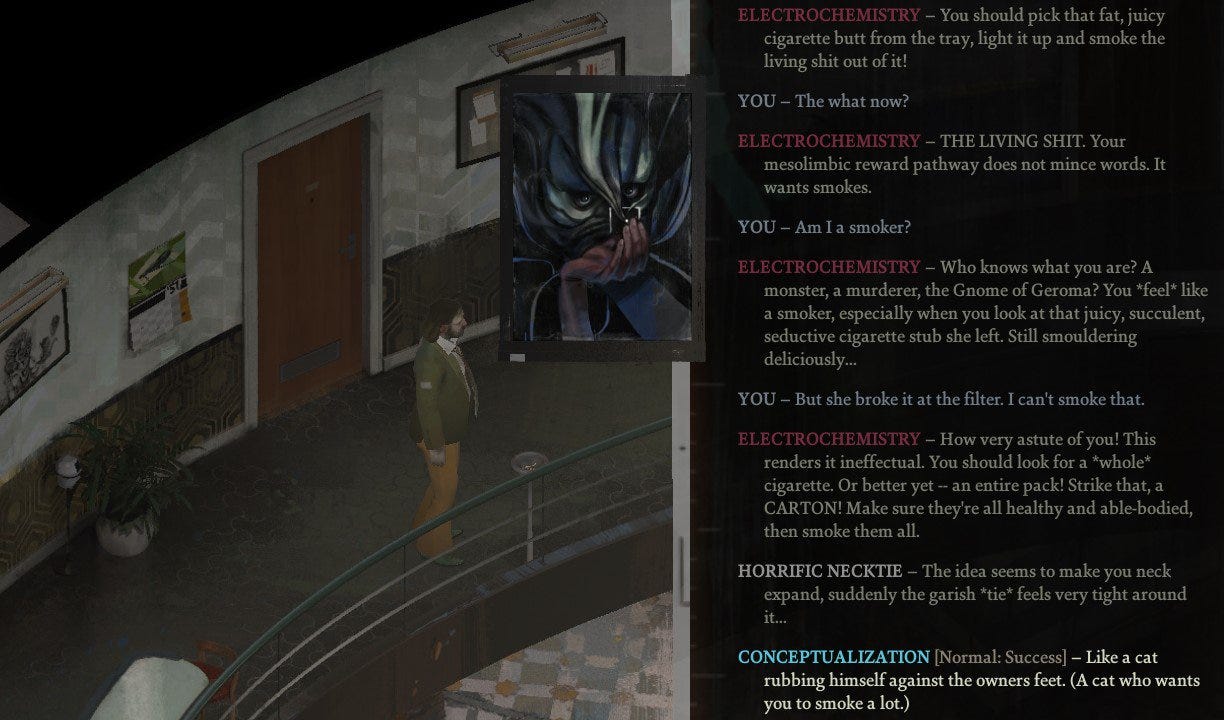

This especially became an issue during the ‘90s and ‘00s, when graphics were just reaching a point where they could sorta depict facial animation and they could sorta have full animation for every figure talking to you, and they sorta had lip-syncing. But games with a lot of talking NPCs would just have a crude figure repeating a canned animation, maybe with a fixed expression throughout their lines, and crude mouth-flap lip-syncing.

On paper, this was a clear step up from the spot-animated pixel-art illustrations of previous generations talking NPCs, but it was a step directly into the uncanny valley, and it made dialogue spoken by these characters feel artificial. Sure, it was a greater technical achievement, but the experience often felt worse than having no visual or audio performance at all.

Add to that the fact that games were growing in size, and how these processes were developed to allow for a huge amount of extra dialogue to be created easily and quickly — meaning that players were now inundated with this sort of dialogue, often repeated, and often doing very little to advance the plot or tone of the game.

When a character is shown as an illustration or cartoon, or their voice is replicated with simple chirps (as a lot of Nintendo games do), then it’s easy for the player’s brain to interpret that as they see fit. And if they’re otherwise enjoying the experience, their subconscious will interpret the experience in a generous fashion, filling in the gaps in the experience with what they’d like to imagine.

In many ways, getting the player invested enough to do this work is the ultimate trick at the heart of any good storytelling.

In most big games, each side of this triangle is the work of a different team of developers. The writers/narrative folks write the dialogue and scenario, the voice actor and audio folks handle the audio performance, and animators/performance capture people handle the visuals. It’s a rare studio that puts equal effort into every part of this process, and there are far too many places where these teams don’t work very closely.

Now, we’re beginning to see studios that can climb up the other side of the uncanny valley, usually with cohesive performance capture setups, like the stunning work that Guerrilla Games has shown in the Horizon franchise. But this kind of achievement is the work of a dedicated team with exceptional technology and effort, which is hard for others to reproduce. And even so, full performance capture is a slow process that makes it expensive to make late changes to any scripted dialogue later in development.

But is this sort of expenditure necessary to make dialogue that connects with a player? Where’s the edge of the uncanny valley, and why can you get away with a deliberate cartoon but not a so-so 3D model?

Implied Description vs Explicit Depiction

As games went from text descriptions to increasing scopes of realization, less and less of the work was left to the player’s imagination. Rather than describing an ominous and bleak alien city, you got a rendered view of it from a tower. And while the technical feat of it was impressive at the time, it narrowed the realm for exactly how much the player could interpret the experience for themselves.

This is the difference between an implied description — painting a scene with words, or only describing a monster by the sounds coming from a darkened doorway — versus an explicit depiction — showing the subject in full detail.

Now, while explicit depictions make for bigger spectacle (and better screenshots), they doesn’t engage the audience’s imagination the same way as a well-delivered implied description. Nothing you can show your audience will be as impressive as the thing they can imagine — and even trying to do so is going to be far more expensive.

Horror movie fans have known this secret for a long time. It’s why it’s vitally important that they don’t show the monster in full until late in the movie — ideally, when it’s time for them to be defeated. Whether it’s the shark from Jaws or the Xenomorph from Alien, these monsters are seen only in shadows, or on their edges, their fins or tails acting as a synecdoche for a full terror that the audience can only imagine.

And indeed, horror games are the ones that still handle this balance best. As a genre, they know exactly how important it is to maintain their tone, and how much full depiction can undermine that sense. From the monsters of Amnesia that you have to avoid looking at, to the deliberate writing guide of Sunless Seas which stresses the importance of suggestions and implications over overt explanations. Giving a full depiction of the space, the creature, or the scenario robs it of the blank space where the imagination fills in the details.

In all of these cases, we see how harnessing the player’s imagination through text or limited depiction can be much more effective (and much less expensive) in making a memorable experience. We see how a well-crafted suggestion of an experience can feel much stronger than a state-of-the-art recreation. And we see how failing to capture one aspect of an experience like dialogue can make every part of the experience feel like a failure.

In game writing, it’s often a case of less being more.

But there are even more insidious paradoxes of the craft. And we’ll get into another one next week.

This article covers all points quite nicely, and there's not much to add. I suppose I could make a semi-Orwellian observation about the effect of the so-called "marketplace" (which seems to be mostly based on the apprehensions of investors and management) on the level of craft. The imagined need is for "bigger and flashier", and it's nothing new: when motion pictures developed sound, there came a lot of all-talking, all-singing, all-dancing spectacles, many of which were lacking in story, substance, or characterization. I am reminded of that time because the production on most graphically advanced games is very similar to that of motion pictures or high-end television productions (with even more alternate versions). Temporarily adopting a Lamarckian perspective, I wonder what effect this will have on the intellectual level of the gamers themselves.