The Number Goes Up: Intro to Idle Games

Games you barely play, but keep thinking about

After completing Expedition 33: Clair Obscur and drying my tears at its tragic beauty, I decided I needed something a little less emotionally draining. In fact, I thought I’d take a brief break and play something with absolutely zero emotional content. Something satisfyingly mindless.

So I picked an idle game at random.

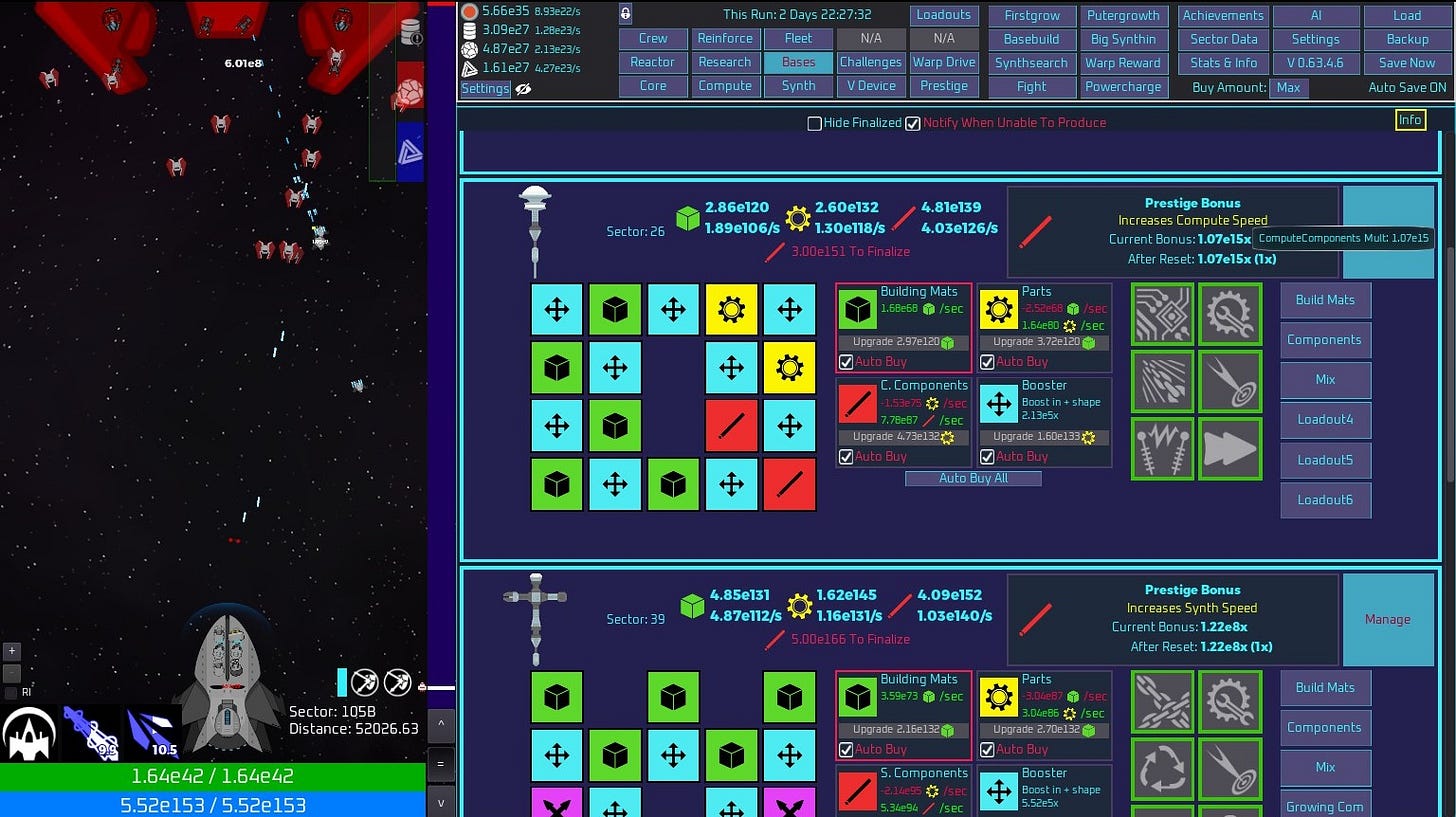

Now, three months later, I’m still playing it. I find the mechanics fascinating. I study how the progress is both compelling and infuriating. I wince at the UI and art, as ugly as the worst clichés of programmer art. I see it as almost entirely empty of any story, to the point where it has almost no proper nouns at all to have a story about.

I have over a thousand hours logged on it. I know there’s no actual end to it.

I hate it. I’m still playing it.

So let’s talk about it.

Today, I’ll give you and introduction to what idle games are, both in their early versions and in their modern, almost weaponized forms. In future articles, I’ll talk about the psychology of how they work, and how (and if) they can be used to tell stories.

The Number, It Goes Up

If you’re like most decent people, you might not even know what an “idle game” is. And idle game, or technically an “incremental game” is a game where your progress is slow but automatic over time, and you play by spending resources to buy new ways to gain more resources faster.

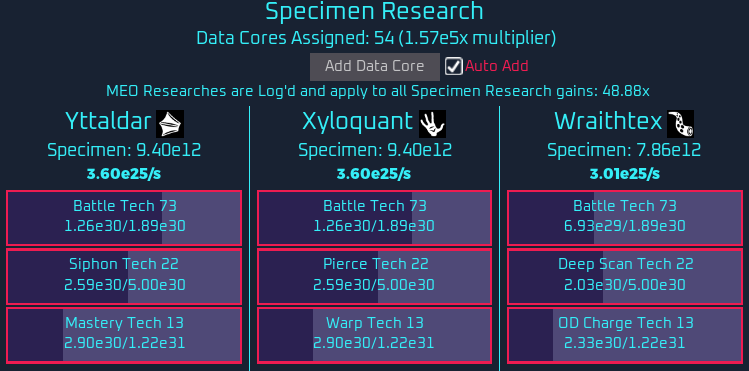

As you go further an idle game, you’ll go from measuring these various resources by the tens, to the thousands, to the millions, and beyond. Get used to reading scientific notation, because when you’re dealing with multiplicative bonuses and exponential increases in costs, that number will be going up very quickly indeed.

You haven’t really gotten started until you’re looking at a resource income at “3.60e25/s” and doing the math about how many seconds it’ll be before that takes your current investment of 1.26e30 points up to the next plateau at 1.89e30. (That’s about 5 hours. Go to sleep and come back in the morning.)

Obviously, “play” is a somewhat contestable term there. It’s not an action-based experience. You spend most of your time letting the game idle as you gather resources between buying new things. Thus the name of the genre.

In practice, it’s a good style of game to have running in the background or on a second screen, and you check it every couple of hours to spend some resources, make some adjustments, and then let it get back to running without your attention. Except you’ll probably end up watching it run for a while, seeing how your changes have made a difference, and micro-adjusting them with pride. And if you’re not careful, you can spend a lot more time making those adjustments than the simple couple of minutes you originally planned to pay attention to it.

It appeals to the sort of player who sees a huge RPG upgrade tree and likes pouring over how to spend their skill points to find clever combinations to maximize effects. An idle game is basically an excuse to do that sort of spreadsheet calculation every couple hours — and can be compulsively addictive to those who enjoy that sort of thing.

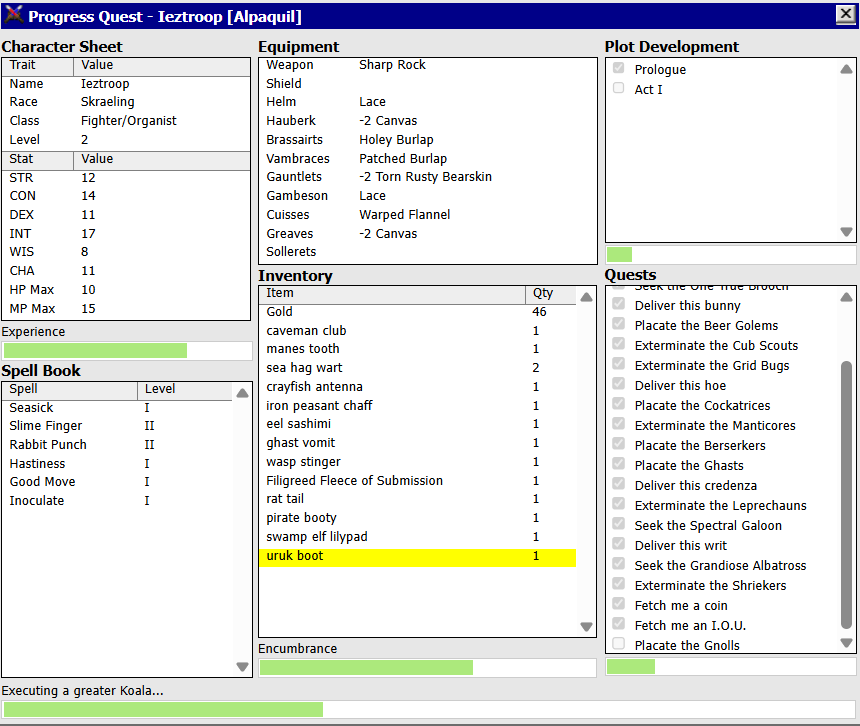

You can argue about the lineage of the “first” idle games. I’d say the modern format was pretty firmly set by Cookie Clicker (Julien "Orteil" Thiennot, late 2013), but you can see a lot of the first steps towards finding what works as gameplay here. But that was also just the most successful of a trend of web game that followed a web game called Candy Box (“aniwey”, early 2013). And, arguably, the whole “just let it run and the game plays itself” genre owes a debt to Progress Quest (Eric Fredricksen, 2002), a satirical “self-playing RPG” built to mock increasingly formulaic RPGs of the Everquest/MMO era.

I’ve had games of Progress Quest that I let run in the background of a computer for years. I’d check in every month or two and have a laugh at the procedurally-generated quest names (“Fetch me an IOU”), or the increasingly ridiculous equipment descriptions (ah, my +3 Festooned Kevlar Brassairts!). It was always a harmless little silliness, and only occasionally a distraction.

But as the genre has found success and inspired copycats, a little silliness isn’t enough. Because…

The Number Demands Your Attention

Now, a free game that runs in the background for your amusement is fine, but in the modern attention economy, the only business model that profits by being run in the background is malware.

Nowadays, these games are still usually free, but they need you to keep coming back to them more often and for longer, whether that’s to watch ads or to increase your chances of giving in a buying a time skip or other microtransaction. The attention economy, everybody!

So modern idle games have done an excellent job give you more things to do in what is ostensibly a passive sort of gameplay. They give players a wide variety of ways to adjust the engine of their progress, whether that means a bouquet of currencies to pursue for different sorts of upgrades, framing progress as a series of waves or stages to advance through, multiple characters or tools to swap in and out depending on the challenge of the current wave of progressive threats, and so forth.

And, of course, the more complexity and categories of options are available, the more opportunities there are to sell microtransations that give quality of life improvements to automate these systems, or to get special skins or characters!

It’s also increasingly common to see a “reset” or “prestige” system where you return to your start, but with an additional permanent multiplier that promises to make it faster to return to your current stage of progress and then reach even further. Think of it as an idle game’s “New Game+”, but more firmly integrated as part of the overall experience.

As a result, the experience of playing a modern idle game feels less like just waiting a couple hours and more like honing optimization strategies and flexing every combination of multipliers until you reach a new plateau. You spend less time simply waiting and more time considering the mechanical advantages of this build vs that, checking wikis and otherwise obsessing over the game and how to get a higher number than you’ve ever reached before.

As you can guess, this is exactly the sort of “dark design” psychological trickery that’s become much more common in the mobile side of the game industry, which broadly leans more towards the “gambling” side of game development’s legacy than the console, computer, and tabletop sides of the industry.

But why does this dark design work on us? We’ll talk about that more in the next article, when we’ve built up enough writing points to publish another one. Looks like it’ll take about 2 weeks of grinding in the background, but I could probably optimize that…

It reminds me a little bit of Duolingo and my PayTrain software, although the "away time" is spent on offline mental drill and rehearsal. In those "games" I'd gather completed modules. I imagine there's a Saint Peter at the Pearly Gates version out there somewhere.