There’s something I mentioned in last week’s article about pinball that may be confusing to people who don’t work in game design: “the toy that lies in the heart of your game”. In fact, there’s probably a lot of game design that makes no sense to outsiders.

So for a shorter article this week, I’m going to introduce a couple vital terms that game designers use in our work. And hopefully they’ll help you understand why some games feel more satisfying than others.

Design and Experiences

Design is the process of organizing a system to have a particular effect in its interactions with a user. For games, this means making something that is pleasing, challenging, or otherwise compelling to play.

Note that this didn’t include the word “fun”. That’s because “fun” is such a subjective term that it’s almost useless by itself, like trying to measure food by whether or not it’s “tasty”. What one player finds fun may feel frustrating or pointless to another player. A designer needs to figure out what sort of fun they’re looking for. They need to know what experiences they players to have.

Many game genres are traditionally built around particular types of experiences, from the power fantasies of fighters to the familiar warmth of cozy homestead games. While a designer can come up with the experiences they want from whole cloth, it’s often useful to build on common genre experiences — both because it’s a recognizable starting point, and because there’s a proven market for them.

For example, a designer making a shoot-em-up might really want to evoke the steely precision of maneuvering a ship through a swarm of shots, the satisfaction of turning the tables on an enemy and using their power against them, and along with the risk-reward promise of pursuing power-ups at the risk of neglecting attacking enemies. In this case, they may look at the shmup classic Mars Matrix as a benchmark to measure their own experiences against).

Once you know what sort of fun you want to evoke, you’ll need something for the player to play with to achieve that experience.

Toys to Play With

Simply put, in game design, a toy is an object and the verbs that players can perform with them.

In early games, these were pretty simple — a ball and paddles, a ship that moves and shoots, a little man that jumps and hits blocks. Modern games tend to have more complex toys — a character who can run, jump, attack, parry, dodge, and so forth. Complex toys, but ultimately just very well-articulated action figures.

These verbs define what game designers call core gameplay — that is, the thing you’re doing every few seconds in gaming. Moving your crosshairs onto an enemy’s head and clicking, bouncing on enemies, parrying and attacking, and all that. To make an compelling game, that core gameplay needs to be viscerally satisfying and versatile, because you’re going to be doing variations of it dozens of times a minute for the many hours of playing.

Once you have an idea of the toy you’re working with, it can be tempting to jump right into making a game around it. But great game designers spend a long, long time refining those toys and that core gameplay before building the rest of the game around it. Legendary designer Shigeru Miyamoto famously spends months refining the details Mario’s jumps and movements (as well as considering the kinetic feel of the controller) before building each of the Mario games that would go on to become such classics.

Designers sometimes call this refining process “finding the fun”, and it’s a constant iterative process throughout the entire development process. You’ve got to know how players can play with the toy in your game before you build everything else — but you’ve also got to keep playing as you build the game to make sure everything you build around it still works with that play experience.

Rules Make the Game

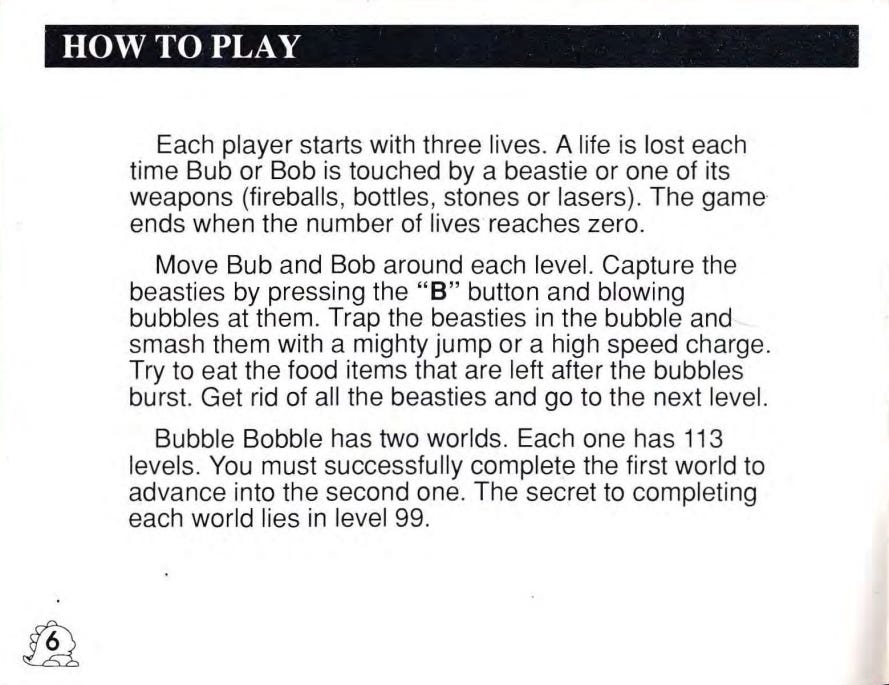

Once you have a toy to play with, you need rules to make it into a game.

The rules determine what the player has to do with the toy you’ve designed. These can be as simple as “move right until you end the level”, or as complex as hundreds of rules about experience, equipment types, skill trees that unlock new verbs for the player, and so forth.

These are the basic rules for playing with the toy you’ve designed. Obviously, these rules need to be something that the player can do with their toy — but more than that, these rules should introduce the player to a variety of ways you’ve found to play with the toy you’ve designed.

Once you have your basic rules, you can then go on to make the levels and scenarios that make up the rest of the game. Things that introduce threats that make those rules harder to follow, modifications to those rules, and other situations that explore the ways to play with the toy and its rules.

From there, you can develop even more abstract things, like the story or overarching changes across the game that reinforce the play experience that you want from your original toy. But remember that you’re ultimately building these things around the toy in the center of your game, so everything has to fit together.

Tools, Letting Players Build Their Toys

Sometimes, especially in more modern games, the core gameplay is less active play and more about building a world or complex system. You can see this in everything from management games like SimCity to Dwarf Fortress to cozier worlds like Tiny Glade.

In these cases, I refer to this as a tool — with the distinction that tools are processes that the player uses to build something they can enjoy, either building rules to enjoy with a separate toy, or letting them build and modify their toy directly.

Sometimes a game is explicitly about using a tool to make a space that you play with, like in Mario Maker or other level-building games. Other times, as in many RPGs, you’ll find that players have both a toy they play directly (their character), and a tool that they use to change what that toy can do (the leveling up, equipment, and general character development system).

Considering most games are already built using developer-facing tools, you may think that it’s a simple matter to simply hand those tools over to the player for this sort of game. But you have to remember that the experience still needs to be enjoyable in its own right.

While a developer may use those tools all day, they’re being paid to do so. For players, you’ll need to make sure the tools are not only intuitive and robust, but also that they give satisfying and immediate feedback. It may be a tool, but it’s still going to be the core gameplay that the player is interacting with for long sections of the game.

If it’s not a joyful experience to work with that tool — something that gives juicy feedback, that players can experiment with before confirming, and otherwise play with — then these entire sections of your game are going to feel like housekeeping. Considering how much RPG mechanics have come to infiltrate every other sort of game, it’s surprising how few games have focused on making the tools in their games enjoyable in their own right.

Forgetting the Toy

So why do I make a point about remembering the toy at the heart of your game? Because it’s a mistake I’ve seen made in major development. When you’re deep in the middle of a grueling development cycle on a game, especially if it’s a game that’s sticking firmly to an established genre, it can be easy to focus more on those rules than on the toy or tool itself.

This is an insidious risk, because when you’re deep in development, it can seem like the smart move. If you’ve been building your game for a year or three and something isn’t clicking — you can’t “find the fun” — at that point it’s cheaper to change the rules around the toy than to adjust the toy at the center of things (because everything else would have to be adjusted for the new changes). But before long, you find yourself changing levels or systems to fit what you feel like the genre expects, rather than what’s actually enjoyable about the toy, and spending more effort with changing things around the edges than you’d have spent if you just considered the core issue to begin with.

This leads to what Design Delve calls cargo cult design — making games from the outside-in, by adding game elements and systems that you expect for the genre without understanding how they work or why they’re enjoyable.

And if you don’t know how you want to play with the toy in the center of your game, then players won’t either. And they’ll go looking for another toy.