Year in Review: Metaphor: ReFantazio

A silly name for a serious fantasy with refined systems, a bold look, and a clear message.

I played Metaphor: Re Fantazio in the autumn of this year, between searching for work and fretting about my country’s election.

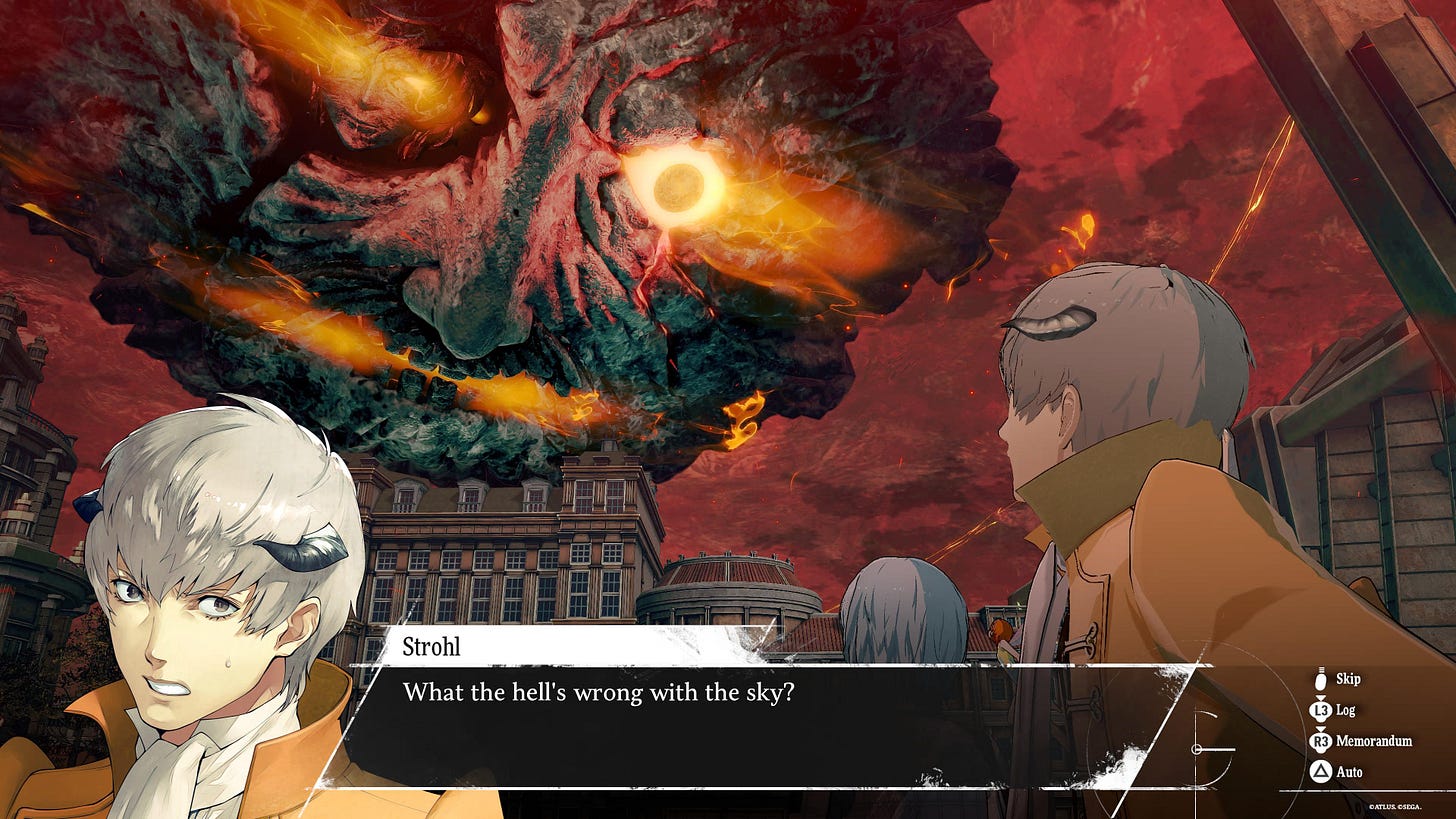

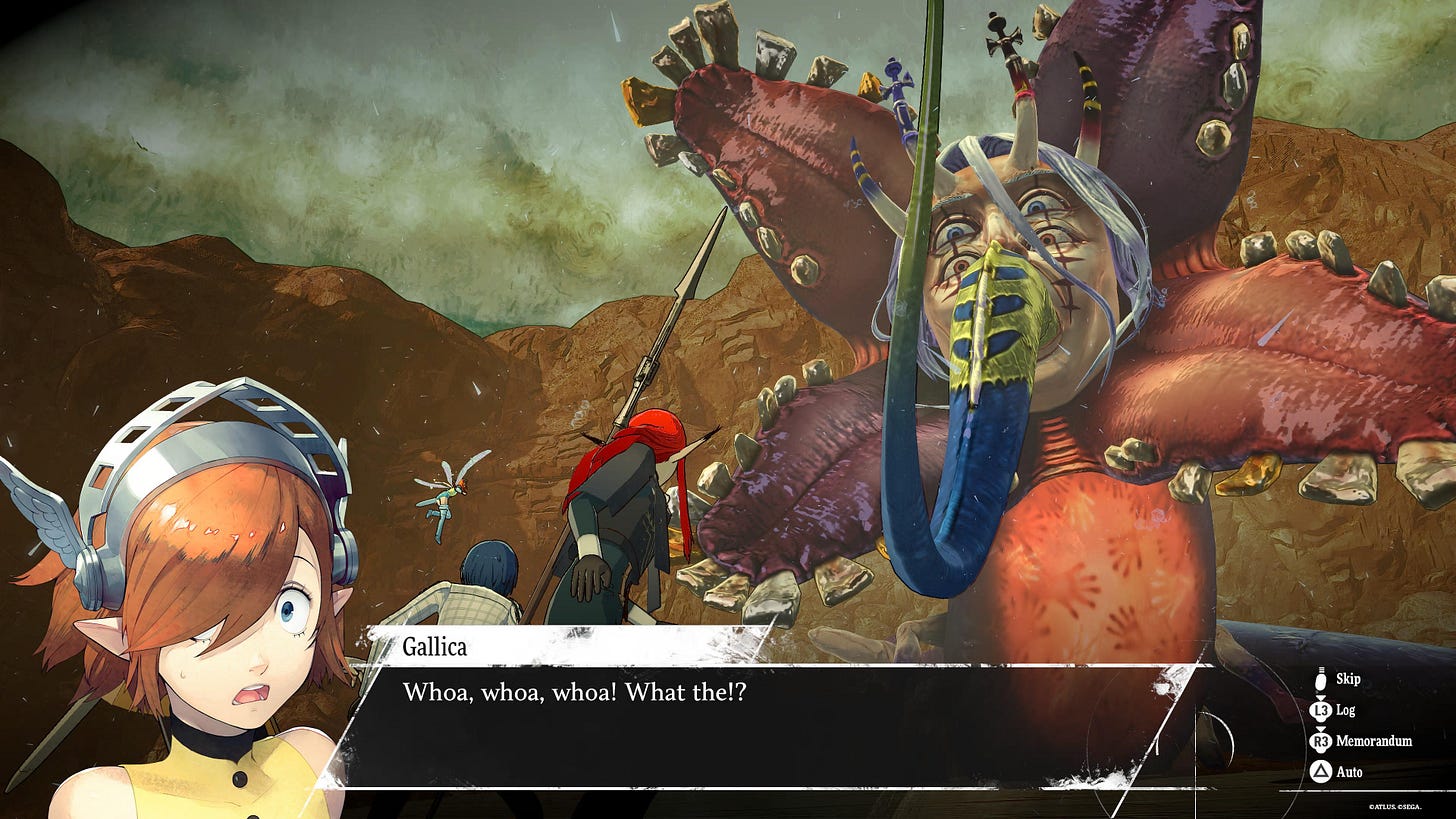

Despite my frustrations with common aspects of Japanese RPGs (the grinding, the interminable lengths of non-interaction, the celebration of “work dedication” as a core gameplay skill), I was drawn to the game by its strikingly different art style — combining the bold UI of the Persona games and creature design explicitly drawing on the work of Hieronymus Bosch. I am still a big art nerd at heart, so anything with Bosch’s monstrous egg-men and berry-eating critters will go on my list.

But once I had waded through the excruciatingly long introduction, what I stumbled into was a surprisingly thoughtful and relevant game, discussing the difficulties of community, leadership, public corruption, and electoral politics against cruel demagogues. Painfully relevant for an American in this particular election year.

At least the game had a better outcome than 2024.

Metaphor: Re Fantazio (2024, Atlus, Studio Zero)

What Is It?

Metaphor: Re Fantazio, or just Metaphor for short, is a highly polished JRPG from the team behind the well-loved Persona series, combining well-refined systems of social/schedule management with turn-based battling. Along the way it has a world full of cities, collectables, NPCs to befriend and betray, side-quests, cinematics, shocking reveals, bonus dungeons, and all the other trappings you’d expect from a top-quality JRPG vying for about 120 of your hours of attention.

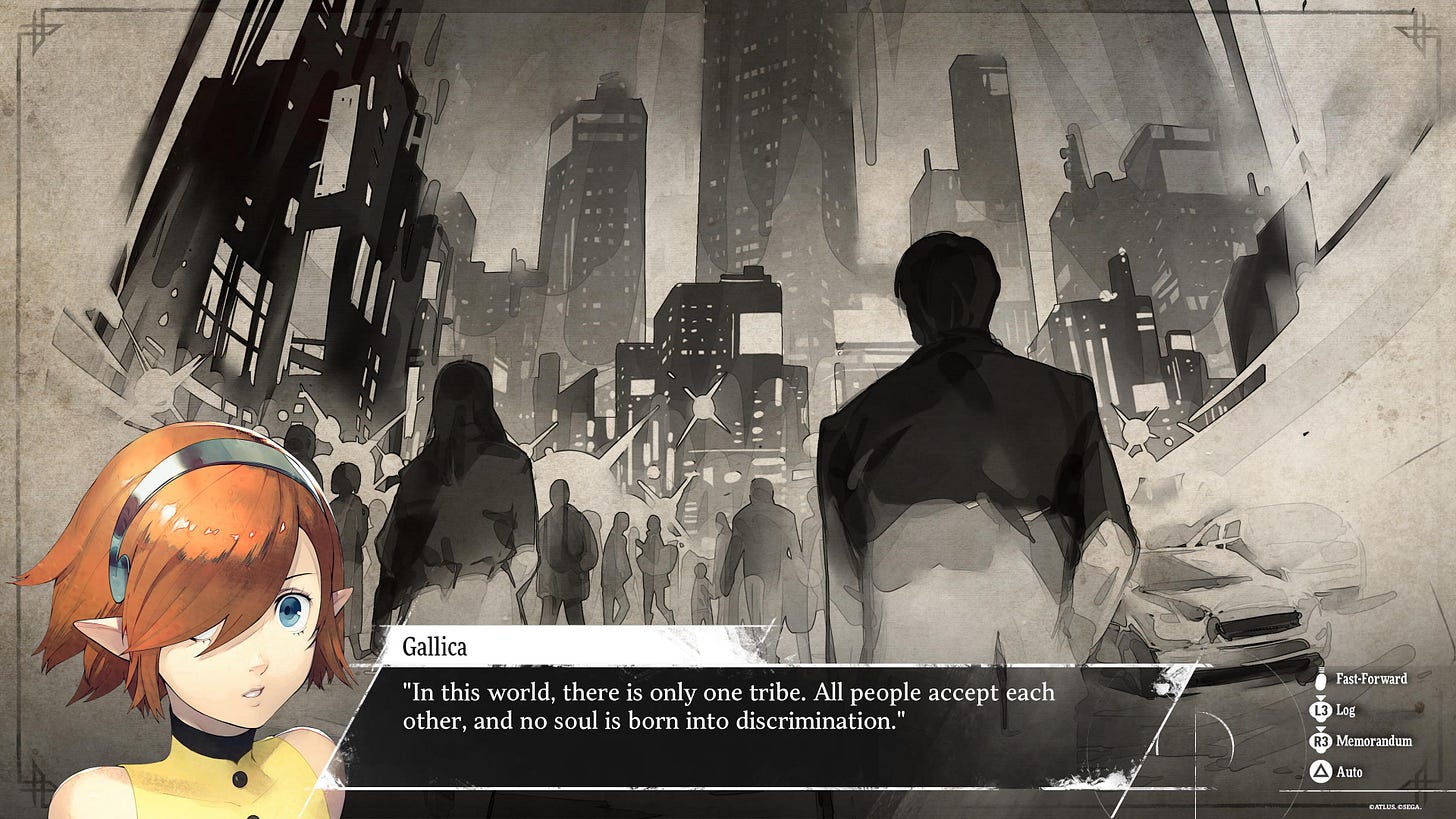

The story depicts a fantasy world of magic and monsters, where fantasy humanoids live in a highly racist and stratified society. An ancient and corrupt church controls much of society and a dying king uses his magic to ensure that the next ruler is chosen by the will of the public. It also includes a novel-within-the-game which depicts a “fantasy” of a modern world where all people live in utopian cities, racism is illegal, and the government is chosen by the people. There’s some interesting stuff here, and it’s clear that the game isn’t afraid to address some big issues.

And so, it’s a tale of how the player and his ragtag group of allies run for a fantasy-presidential election on the platform of “care about everyone and help them” against popular juggernauts like “the church should continue to rule everything” and “only the strong deserve to survive.”

This is the sort of thing that might feel awfully on-the-nose if it weren’t coming from a Japanese game that’s been in development for years before our current news cycles — and if it wasn’t dealing with the sort of nonsense that seems to have become endemic across the world. It’s also delivered with the sort of grandiose drama you’d expect from a good anime: every threat is the end of the world, every revelation is a deep truth about the nature of reality, and so forth. Eventually, “the evil strongman nemesis” feels less like a reference to your blonde-haired-demagogue of choice and more like a universal archetype.

In terms of gameplay, the elements of this game aren’t revolutionary, but are well-refined enough to keep the game exciting. The schedule-management half of the game is straight out of Persona, as you take time talking with allies in different cities, growing your social stats, pursuing friends’ sidequests, and otherwise finding time for all of the non-monster-killing responsibilities of a hero.

Meanwhile, the dungeon-crawling, turn-based-battling half of the game is pretty familiar, but with one or two simple changes that reap excellent rewards. Most notably, in your turn-based battles, hitting an enemy with a critical or an element they’re weak against only takes up a fraction of a turn. Meanwhile, missing an enemy or hitting them with an element they’re strong against takes extra turn actions. And these rules apply to the enemies as well. As a result of this simple change, you’re hugely rewarded for knowing your enemy’s weaknesses and preparing your party appropriately. It allows you to face much more challenging enemies and win through clever fighting, changing battles from the fairly simple resource-management challenge they usually are into much more interesting strategic puzzles.

It’s a big difference, brought about by small rules changes, and that sort of thing is the dream of a good systems designer.

So, story, schedules, and swordfights. The archetype of a JRPG, albeit with a more relevant story than most.

What Makes It Stand Out?

The visuals are certainly the first thing about the game that stands out, although they’re hardly its only strength. Anyone familiar with the Persona games will be familiar with its style of bright and bold UI spraying forth from characters in battle, along with beautifully rendered, painterly status screens. It’s gorgeous, it’s lush, and it’s a great way to draw new players into the game — even if you sort of stop noticing them after your 40th hour of playing.

In fact, I think that the game’s lineage, from the people who have brought you half a dozen Persona games, may be the thing that put this game on the radar for most JRPG players. And that interest will definitely be rewarded, as the game plays very similarly in its alternations between scheduling-and-battling, which build a nice rhythm for the experience.

Except in this case, you’ve got fantasy-medieval politics rather than Japanese-highschool drama. But the two seem less dissimilar than you’d expect.

What Does and Doesn’t Work?

The aforementioned art really does sell the game well, and keeps things feeling dynamic. And while you eventually get used to it, I don’t think anyone can doubt that it works. I can only imagine how much work and planning it took to lock down some of those screens in time for the artists to truly give them the business, but from the players’ perspective, those are unmitigated victories.

Then there’s the battling. I’ve mentioned the cleverness with the turn-based battle system, and it’s really worth highlighting because it’s a triumph of design to solve a moribund old problem of turn-based RPGs. Sadly, there’s another classic problem of the genre that they also tried to solve, but with less success: grinding.

When you enter a fight with an enemy group that’s several levels lower than you, they just die in a flash and you get the minor rewards you would have gotten if you had fought them normally. Other games have done this before, and it’s a great way to keep players from being bogged down with battles that have little consequence. But it also makes it easy to grind through lots of enemies to farm experience or rare items.

Now, going into dungeons takes a lot of your schedule time, so you’ll find you want to limit the number of times you actually go dungeon-delving to when it’s really important for the story, and designers may recognize that there’s an economy of magic points to limit how long you can stay in dungeons in any single run.

In theory, this is supposed to prevent you from constantly grinding for levels, keeping your characters in an optimum level range at all times and keeping things balanced. Unfortunately, the system is pretty easy to exploit and overcome, and instead you may find yourself running around dungeons you’re overleveled for, killing monsters by the dozens, waiting for them to respawn, and then repeating — maybe even for hours at a time. All of this to ensure that your characters are prepared to make it through the larger and more plot-vital dungeons in a single trip later in the month.

Even when a JRPG tries to prevent players from grinding, the rest of the gameplay encourages players to find a new way to do exactly that. Alas.

Still, there’s one element that JRPGs live or die on, and that’s the quality of their story. It’s a broad positive for me, but not without qualifications.

The writing itself is hit and miss, occasionally even at the same time. Sometimes excellent philosophical ideas will be expressed in the dumbest ways possible; sometimes wildly frustrating plot twists will only feel justified by surprisingly delicate and touching scenes that follow. Generally, the writing has enough interesting ideas in play, and enough enjoyable characters voicing them to make the experience worthwhile, but you’ll definitely have your moments of wanting to move on. Sure, there are too many characters and an index of Proper Nouns that you could club a monster to death with, but the core story holds together well enough without having to consult it, and it sticks with you pleasantly after the game is done.

Strangely enough, I’d be a little surprised if there are any direct sequels to this game, because it’s a story and setting that wraps everything up and doesn’t really leave any mysteries or plot hooks left for future tales with the same characters. This is a self-contained package, and the fact that a one-shot experience comes alongside such a highly-refined gameplay is a rare combination in this sequel-dominated industry.

But ultimately, I think the biggest issue with the game is one that you see in any game that goes over 100 hours, and especially JRPGs: there are moments that drag, gameplay that feels repetitive, or just scenes that are incredibly slow. Conversations where you’ve already figured out what the players are being shocked to learn about and over-explain, and you’d just. very. much. like. to. get. back. to. the. gameplay. please. And my personal pet peeve, the major battle where you fight valiantly to victory, only to immediately go into a cutscene where you cinematically lose. I didn’t mind my time being disrespected like this when I was a kid with long days free on summer break, but nowadays I feel like a game has to earn every hour I can set aside for it.

What’s It Saying?

One nice thing about the habit of over-explaining everything in a JRPG is that you never have to be unsure of its message.

And this is a game with explicitly political messaging. It talks about about what a good leader should be and how a good society should behave. Multiple political ideologies are represented among your competing candidates, although most of them are either presented as laughably extreme caricatures (“No taxes, no laws, no religion!” says Roger the Libertarian), or assorted benevolent figures who join under the player’s banner of “Try to help and care for everyone”.

This is not a game that hides behind the lie that “our game isn’t political.” And thank goodness it isn’t, because that lets it actually say what it’s saying in a clear voice.

Of course, this fairly milquetoast position of “caring about people” somehow seems to be controversial both in the game and in our world, and its main opposition is the laughably cruel position of “only the powerful deserve to survive”. Painfully prescient that this game came out in 2024, yes, but I suppose some degree of this is universal.

Still, points to the game for reinforcing this message in its gameplay beyond just the story — it’s only by actually working to help all of your supporters, the side quests, and generally every person in the world who has a problem that you’ll achieve the realization of your message triumphing over cruelty — and, of course, the best ending of the game.

But more than this overt message, the game is about the necessity of a fantasy (or Fantazio) as a guiding star, so that those who do truly care and strive can have a unified vision of what they’re striving for.

And in its way, this game is explicitly trying to be that fantasy for a generation of players. Honestly, more games should have the courage to do this. It’s certainly what I aspire to in my own work.

Who’s It For?

At this point, it shouldn’t be hard to tell whether or not you’re interested in Metaphor. Anyone with a fondness for JRPGs probably already knows they want to play this game, by its pedigree alone.

But it might be a harder sell for those with little patience for the tropes of JRPGS, people who balk at long cutscenes or who get frustrated at “dialogue choices” that don’t actually make any difference in a conversation. Still, players with an open mind and a fondness for striking visuals or thoughtful storytelling will find something to enjoy.

Even so, getting there will be time-intensive, and busy players without the time or patience to sit through yet another length conversation may want to sit it out. Parents will find it’s not a particularly kid-friendly story, and anyone who can’t carve out a couple of back-to-back hours for gaming sessions simply won’t have time to sink into the setting and storytelling.

Which is to say: this is the epitome of a Japanese RPG, for better and for worse. Take that as you may.