Year in Review: UFO 50

A holiday haul of games that never were, and a glimpse at what games could yet be

The retro 8-bit game is a curious cultural artifact. For some, it’s a powerful totem of gaming authenticity, charged by nostalgia and mystique. For others, it’s a musty bit of unplayable code that belongs in a museum if anywhere. Entire subgenres of gaming are built upon the appeal of its pixelated memories, while it’s common wisdom that other entire sectors (like the Chinese gaming market) hold no regard for retro stylings because the pixelated 8-bit era largely never came to their country.

For me, a gamer who grew up with a Commodore Amiga and a Nintendo Entertainment System, the 8-bit era was certainly fundamental to my gaming development, but I’ve always been leery of giving into nostalgia. I’ll never deny that elements of that era were stamped on my young soul like a gaming passport — the lush parallax-scrolling graphics of Psygnosis games, the iconic battle music of Final Fantasy, the surreal challenges of early Rare games like Snake Rattle n’ Roll or Battletoads — these are things that still thrill me to this day.

But I’m also someone who’s gone back and replayed those beloved classics with a professional’s eye, and seen exactly how much they do and don’t hold up to modern design. Lacking proper curated museums for games of the past, emulation allow us to return to these lost favorites, to see them again unclouded by memory. And for all the fond memories that come from nostalgia, it’s an absolute poison if you let it cloud your thinking.

So I was excited but nervous when I first fired up UFO 50, a collection of “lost games” from the fictional LX game console. They were developed by Mossmouth and friends, a crowd of indie devs with no shortage of delightful and innovative titles to their names. I was excited to see their work, but a little afraid I might find mawkish love-letters to old game styles that were unplayable by modern standards.

Instead, what I found was a developer's manifesto of how varied and gleeful games used to be back when the industry was young and still experimenting, and what they can be again now that they’re cheaper and easier to make.

UFO 50 (2024, Mossmouth)

What Is It?

UFO 50 is a collection of 50 (fifty!) different 8-bit games, presented as an emulation of a trove of long-lost games from the LX gaming console. These games are presented with a complete artificial history of the company, the designers, the evolving characters and game concepts, and a developers’ console with hidden codes to input. The whole thing is presented like an emulator from a old-school warez team that discovered the haul in a storage locker, and the whole metafiction even includes a hidden backstory about the drama of the fictional company behind it all, for those willing to do a little digging. There’s even a little house for your LX simultated gaming buddy, a little character reminiscent of David Crane’s Little Computer People.

Loading up the game presents the player with a dusty collection of diskettes to exhume and play. Each game is a whole and complete experience in itself, played on a classic NES-style style controller, ranging from simple adventure games to shooters to arcade action to simple RPGs. Each cartridge includes the name and date of release, as well as a trivia blurb about the game, and making progress in the game can unlock meta-rewards, from “gold” and “cherry” disks for when you’ve completed or mastered a game, to a piece of furniture for your little LX person’s house and garden.

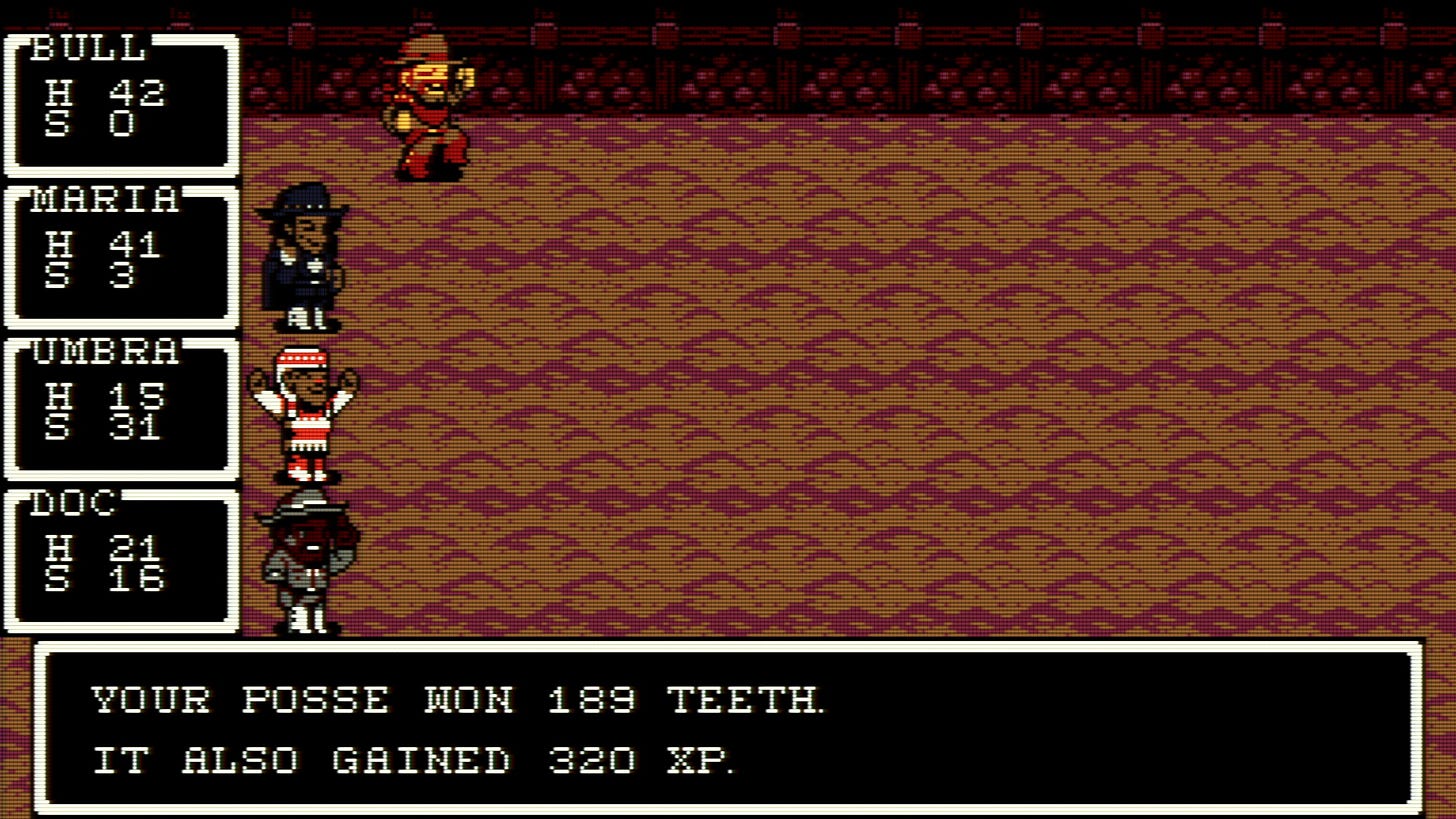

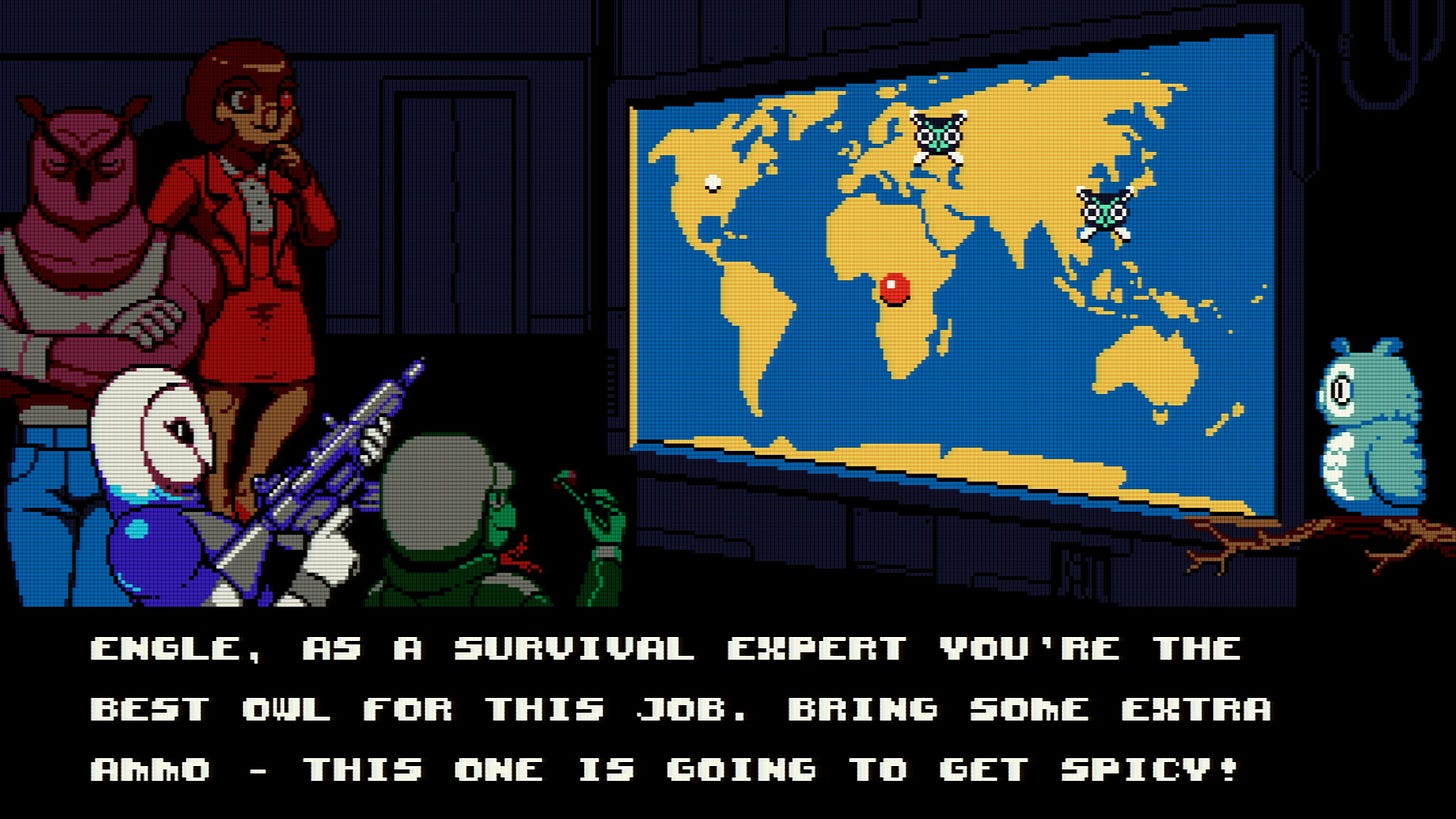

The games themselves, however, are the main attraction of course. Trying to describe all fifty in detail would be a fool’s errand, but anyone who played through the 1980s will recognize parallels among them immediately, from the punishing adventure game Barbuta (reminiscent of Dark Castle and Adventure), to the life-ending puzzle platformer Motrol (Lemmings, with a darker twist), to the point-and-click adventure game Night Manor (Shadowgate, but in a horror/slasher genre), to the party-based RPG Grimstone (what if Final Fantasy was a spaghetti western). Recognizing all of the knowing nods is a certain sort of achievement in its own right.

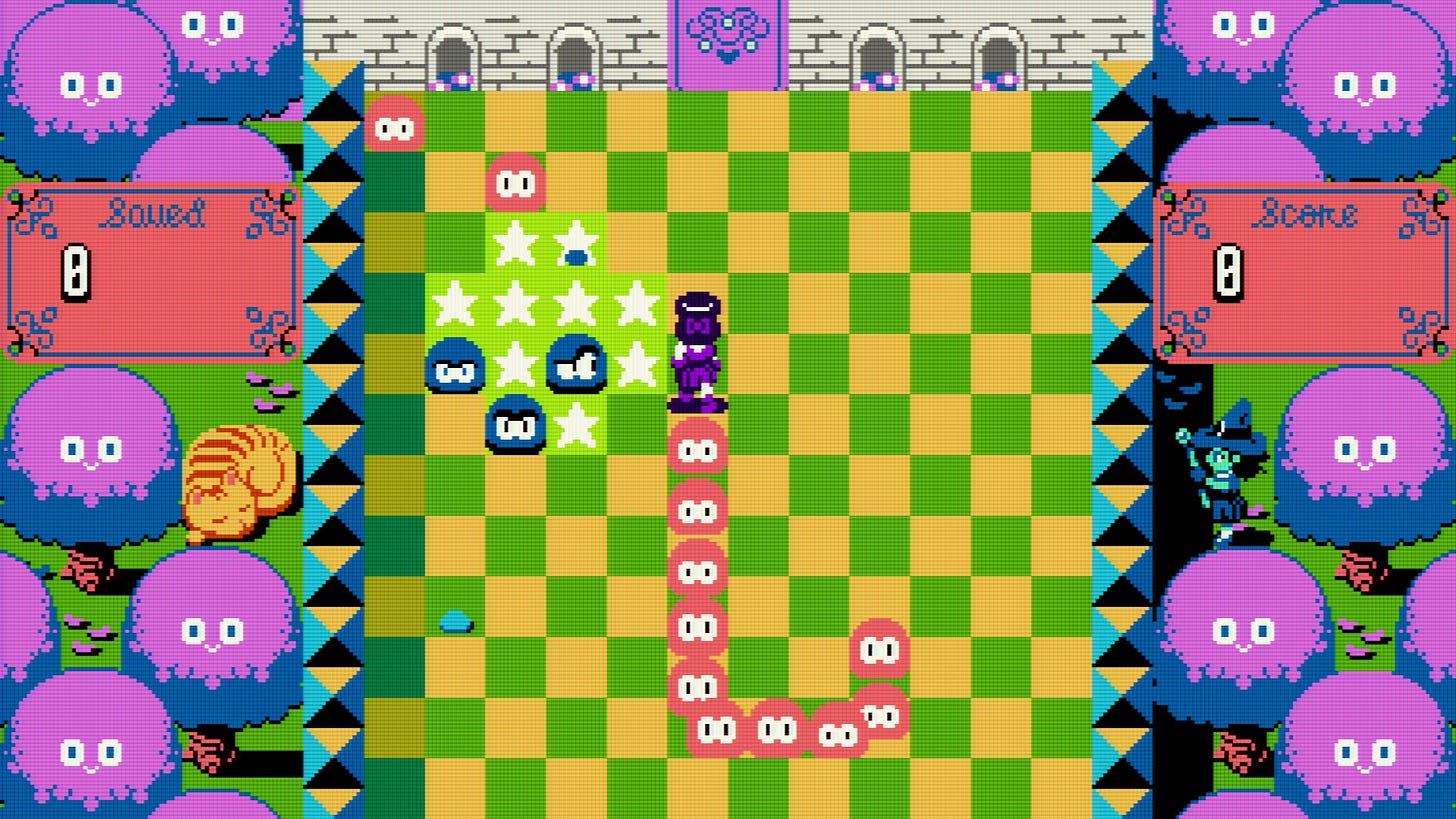

These games are varied enough that there’s likely to be something that’s a hit for everyone, and despite the many nods to prior classics, there are enough innovative new creations to give everyone something to explore. A tactical battle game based on Carrom? A push-your-luck game about throwing the perfect ‘80s house party? 4X grand strategy with dinosaurs? An open-world golf RPG? A microscopic adventure game that takes place all inside a single closet? All of these and more are there for your discovery.

What Makes It Stand Out?

For some, the immediate sales pitch is the retro quality of he games. I’m sure there are retro gamer who find the prospect of an entire fake console and library to be irresistible, and I fully expect to see fans of this game making further fake artifacts from its imaginary era. I’m sure someone out there is artfully weathering a fake instruction manual for Valbrace, or mocking up a day-glo trading card for Seaside Drive. I’m not looking to buy a Funko doll of any of the characters, but it wouldn’t be a surprise if someone made one of their own.

But I’d argue that the more useful sales pitch is the sheer value-for-money of this package. At a full price of $25, this is basically a grab bag of games for 50 cents each. And out of the collection of fifty games, you’re bound to find at least four or five games that you play as much as a normal indie game you’d buy for $10. If you’re measuring by sheer time spent, I played one game (Grimstone, the western Final Fantasy) for well over 40 hours before defeating putting the final boss to rest — that game alone would have offered a good dollar-per-hour entertainment value for the whole package.

What Does and Doesn’t Work?

Being faced with fifty different diskettes and no way to know where to start can be mighty daunting to some. Whether or not the experience works for you depends on how you react to the prospect of finding a big bag of old books or CDs in your parents’ closet. There’s bound to be something interesting in there, if you have the patience to wade through the things that don’t catch your interest.

There’s also the matter of the games’ very period-accurate difficulty. That is to say, most of these games are brutally unforgiving: split-second shoot-em-ups, arcade games without continues, and lots of action games whose reflexes would have put my younger and sharper self to the test. While they feel like the sort of thing that can be mastered by a dedicated kid with hours to hyper-fixate on a game, that’s not who I am anymore, and I suspect the same is true for other retro gamers who would be drawn to these games. Some of these games, like the shooter Star Waspir, simply aren’t things I think are within my capacity to beat with the reflexes I have left.

And frankly, that’s not so bad when it’s just one out of fifty games. Even considering all of the heavily reflex-dependent games, that’s maybe 10 out of the whole lot, which is fine. With a bounty of games like this, I don’t feel the need to master all of them. But I do kind of wish that the developer’s console included something like a save-state option, or even the old crappy “slow-mo” you could get with a pause button set to rapid autofire. Just so I could give it a shot, y’know?

Honestly, I feel like the developer’s console could have had a lot more functionality available to it, as if it were a built-in Game Genie, modifying the underlying guts of the faux LX system’s code. But I realize that’s asking for an awful lot, especially on top of having already received fifty complete games.

What’s It Saying?

Twitter user @Jordan_Mallory once memorably said, “I want shorter games with worse graphics made by people who are paid more to work less and I’m not kidding.” That passing desire has become something of a rallying cry for both gamers and developers hoping for a healthier and more sustainable game development industry.

UFO 50 feels like a thesis in answer to that request, and a gloriously successful one, at that. Here you go: fifty shorter games, with worse graphics, made by a small team, using the sort of modest budget and schedule that most studios would devote to a single game. And by god, it works.

Bundling a bunch of games together means there’s something for anyone, and gives the designers space to stretch out and get experimental on a few projects (like Mooncat, a platformer where player movement controls are mapped to the controller in a radically different fashion than we’re used to), while making only slight refinements on more traditional games (like Pilot’s Quest 2, which is somewhere between Legend of Zelda and an idle game). It’s a pitch for more studios to embrace experimentation in games, and for them to supplement those experiments with their reliable franchises. Especially when these studios ca use ready-made engines like GameMaker Studio, as UFO 50.

This is how movie studios used to approach their releases: a shotgun approach of experimentation and small films, with the occasional blockbuster and tentpole franchise to provide reliable income. The prospect of smaller, simpler games for cheaper means studios could have space to stretch out and experiment again.

Who’s It For?

Obviously, anyone who’s nostalgic for the retro games is going to be drawn to this like two-pixel bees to an RGB flower. Honestly, anyone who’s deep into that realm has probably already bought UFO 50 long before reading this.

But the real appeal should be to any developer who’s worried about the state of the industry and looking for another path from the unsustainably large quadruple-A games that have been leading to bloated budgets and cascading layoffs. Because UFO 50 proves just how much freedom and experimentation you can embrace when a studio stops trying to make triple-A, photorealistic experiences and instead focuses on make a bunch of fun experiences.

In that way, UFO 50 isn’t just a celebration of a fictional past in gaming. It’s a potential roadmap for its future.