Like so much of the gaming public, I’ve spent the last couple weeks playing Clair Obscur: Expedition 33, the unexpected and overwhelming new game from French developers Sandfall Interactive.

And rather than repeat all of the well-earned praise it’s gotten from everywhere else in the media, I’d like to take a look at how one deceptively simple game mechanic makes the experience such a radical change from the JRPGs that have clearly been such a clear inspiration for it. But I promise not to give any spoilers for the game’s beautiful story of grief and being wistfully doomed in a very arthouse French way — at least, nothing more than you’d get from the opening cinematic.

But first, I’ll have to set the stage a bit.

JRPGrinds

The JRPG, or Japanese Role-Playing Game, is an institution in gaming, and I have a long history with it.

It goes back to playing the original Final Fantasy on the Nintendo. I cried to Nobuo Uematsu’s masterful opera house music in FFIII (back before I knew it was actually FF6). I fondly remember the Square PS1 era when they released a dozen experimental JRPGs as a way to test mechanics for their flagship series. And I lived in a college group house that had no fewer than three of us fighting for time with the only TV to play our own separate saves on Final Fantasy 7. And then again for Final Fantasy 8.

Somewhere, around the twentieth hour of watching friends use FF8’s infamous Draw system to stock up on spells and grind up levels, the allure of the genre finally faded. And as much as I enjoyed FF9’s throwback style, by then the genre had begun to sour on me.

The same thing that appealed to my patient and obsessive brain in my time-laden youth became much less appealing as I graduated and collected other time commitments. As much as I appreciated that any obstacle in the game could be overcome by patiently grinding away for levels and loot, it became clear that this wasn’t just one play option, but the only option.

I came to an unfortunate conclusion about the JRPG genre: that its 100-plus hour games were not so merely about testing a player’s cleverness or tactical skill, but a test of their commitment and masochism.

Want to beat the boss? Want to beat the optional, bonus bosses? Want to get the real ending? Then you had better be willing to put in the time fighting dozens and hundreds of fights to max out your stats. Otherwise, it’s just not numerically possible.

And yes, I know that’s not always the case. But it certainly was common enough to make me lose interest. And so, I slowly fell out of love with the JRPG genre.

I’ve mostly stayed a spectator for two and a half decades of Final Fantasy games, occasionally dipping my toes into other franchises like Persona and Metaphor when a new champion arrived and I missed the sweeping stories and grandeur of the genre. And I had the spare time for the grind, of course.

And then came Clair Obscur.

The French Connection

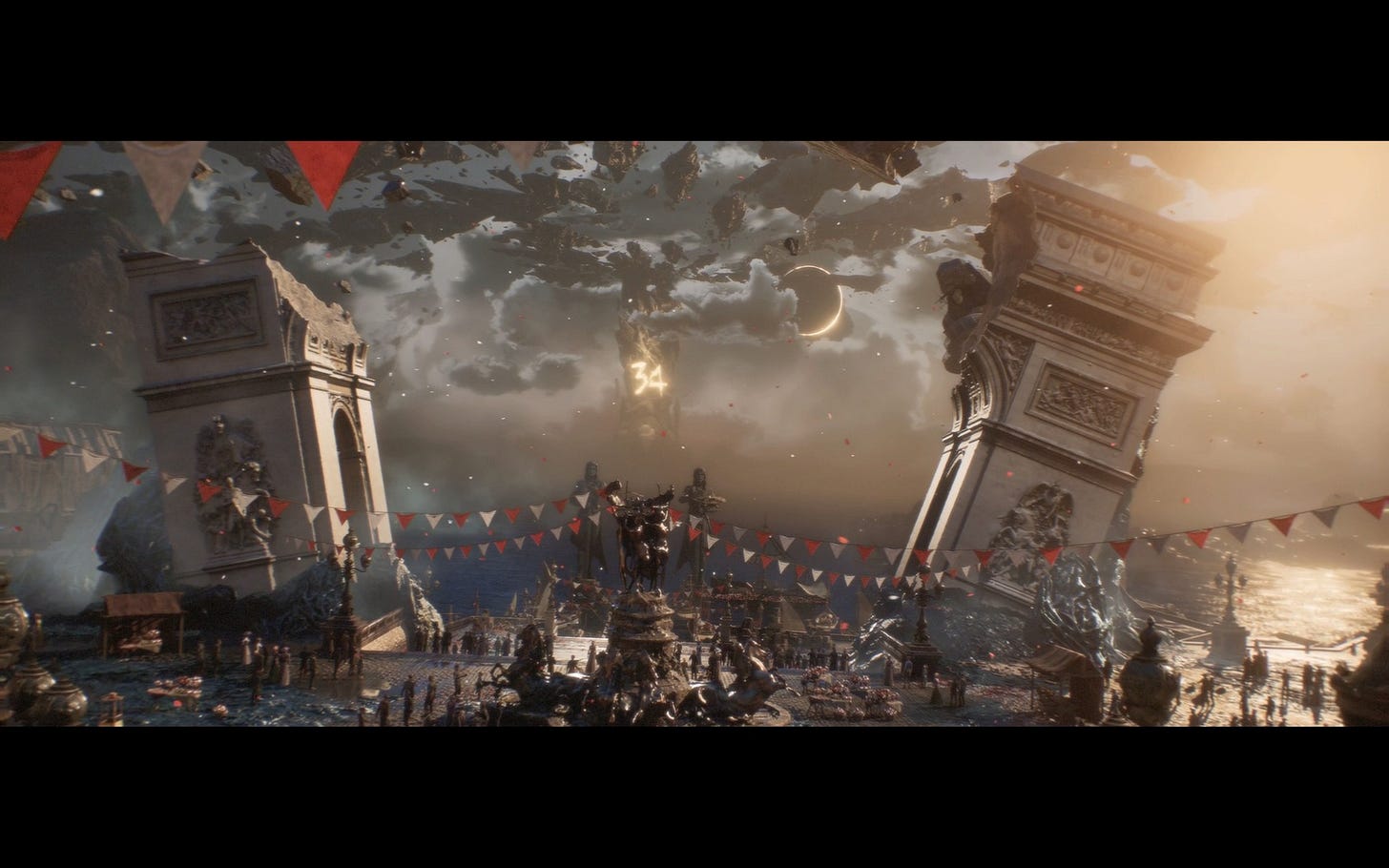

In case the similarities aren’t clear from the trailers, Clair Obscur: Expedition 33, is a pitch-perfect JRPG, particularly in the modern Final Fantasy mold — so much so that I was able to describe its story and gameplay beats by referring to Final Fantasy analogues: “Oh, I won’t be dealing with that until I’ve got an airship, okay.”

But this FRPG has two big exceptions:

Firstly, It’s French, which seems to make some of the translations easier as the writing consistently connects better than FF games, whose translations are often notoriously questionable. Also, just as JRPGs will abruptly include Japanese cultural cliches like samurai and ninja in their games, Clair Obscur includes French cultural cliches, like fighting mimes and unlocking berets and old-timey bathing suits for characters. I’m surprised that these doomed expeditioners aren’t all chain-smoking Gauloise Blondes, but I suppose that sort of thing ups a game’s age-rating nowadays.

Secondly, and more substantially, it adds active combat mechanics to the traditional turn-based combat. In this case, it’s a particularly a robust dodge-and-parry system that it expects players to make heavy use of: during combat, any character can attempt to dodge or parry attacks that are aimed towards them.

This is done by pressing one of two buttons (although more variations get added as the game continues), and if you do it correctly, your character takes no damage from the attack (or at least that hit of the attack, as enemies quickly progress to having much longer attack chains). There’s even a small risk/reward calculation involved — dodging an attack gives you twice as much time window for success than the very brief timeframe for a successful parry, but parrying gives your character a chance to counterattack and other various benefits.

And that’s really it, mechanically. Otherwise you’ve got very much the same sort of deep tactical build options and complexities of a good JRPG.

But you’d be surprised how that one mechanical change addresses the issue of grind in the genre.

Changing the Game

See, combat in most JRPGs — and many other classic turn-based RPGs — ultimately becomes a game of resource management.

Let’s say that everyone in your party has X number of hit points, and each enemy attack tends to deal 5-10% of those hit points. You can restore hit points with spell points (or items), but those are even more limited, so it comes down to figuring out how to make it from checkpoint to checkpoint while keeping your party alive and ready for the boss at the end of the level.

Changing your gear and abilities can make a big difference, but ultimately you’re always finding a way to manage your loss of those hit points and spell points, whether your setting is sword & sorcery or science-fiction. And ultimately, the way to make those resources last longer is to spend time fighting enemies and levelling up so that you have more assorted points to work with.

Adding action responses in combat can shift that consideration a bit — I think the first time I saw a “press button to time your block” option was in the Super Mario RPG, but it was mostly a way to add a little action to fights that otherwise played out a lot like other JRPGs of the time. It mitigated small hits, but wasn’t always an option. And while other JRPGs have made similar experiments, I’ve never seen them fundamentally change the nature of the combat experience from this tactical resource management challenge.

But in Clair Obscur, enemies always hit hard. Even in the early stages, a single enemy attack on your expeditioner may take a quarter or even half of their hit points… but only if you fail to dodge or parry that attack. And you’re always able to try — encouraged even, since there’s no cost for failing a dodge or parry beyond the damage you were already going to take from the hit.

Early on, it’s pretty easy — enemies make a big show of building up for one or two clearly-signalled attacks, and it’s pretty easy to dodge them, since dodging has twice as much of a timeframe to protect you than parrying does. But dodging gives one of three feedbacks:

You get hurt (which means you completely mistimed the dodge)

You get a “Dodge” result (which means you dodged the attack, but only in the extra timeframe that dodges give you versus parries)

You get a “Perfect” result (which means you dodged the attack in the timeframe that a parry would have worked)

Once you recognize that, you learn that Dodging is a way to practice your Parrying, and once you start getting a lot of “Perfect” results against a particular enemy’s attack, you’ll want to switch to trying to parry them, instead. And that’s because successful parries not only prevent you from taking damage, but they give you more Action Points (think spell points that are constantly recharging) and parrying an enemy’s entire attack sequence delivers a devastating counterattack — which can often be more powerful than your normal attacks.

So when you’re adventuring through a dungeon in Clair Obscur, you’re not focusing on managing your hit points as much as you’re focusing on learning what to expect from the new batch of enemies that reside there. In addition to the standard tactical considerations like what elements they’re weak against and which enemies are higher priority in combat, you’re learning to dodge and parry their increasingly complex attack sequences.

Hopefully, by the time you’re coming to the end of the dungeon, you can fight any number of its enemies without getting hit once — and parrying so often that you’ve got lots of Action Points to use on big abilities, and lots of counterattacks to make quick work of the enemies.

So, a combat system that switches from being about resource management to being about learning the enemies and developing your skills at perfectly countering their attacks?

Where have I seen that sort of combat gameplay before?

Don’t Grind, Git Gud

That’s right, it’s a Souls-like. Really should have seen that coming from the Miyazaki-esque enemy designs.

Now, don’t take that “Git Gud” seriously — you don’t need to have killer reflexes to play this game. There’s nothing wrong with turning down the difficulty, or even using mods to make the parrying easier. For goodness’ sake, don’t let it scare you off of such a wonderful game.

Even if your reflexes are only that of a mere mortal, you’ll find that dodging and occasionally parrying will make this a game where you spend more time exploring and less time grinding up higher levels to survive the unforgiving mathematics of the next dungeon’s enemies.

Because even while your characters are levelling up, you-the-player are also noticeably developing your skills against each enemy. And even as the enemy attacks get more complex later in the game, you start recognizing other cues for your dodge and parry timing — learning to listen for audio cues that will help your timing, as well as little build-up animations that signal when an attack is about to connect. In a very clever way, giving you this many cues for such an important gameplay mechanic is also tricking you into paying more attention to the game’s excellent audio and animation — and it’s always a real feat of game design when your mechanics make players appreciate the rest of the game as well.

Now in theory, this means some sort of wunderkind with perfect timing could play through the whole game at low levels without getting hit once. I’m sure there’s someone out there on a Twitch stream showing off those skills.

But in practice, it means that the same patience that once led me to spend hours levelling-up my Final Fantasy party in the Hall of Giants can instead be put to use fighting against a boss that I really shouldn’t, statistically, be able to take. It just means learning the timing for all of his attacks.

And that leads to a victory that feels much more satisfying than one I spent three times as long grinding up to achieve through numeric force alone.

Mind you, getting to that point also includes a fair amount of messing up and dying comically. But hey, the entire game makes a big show about how this expedition has been tragically doomed from the start.

Plus, it adds an extra level of dark humor to see these wistful and stylish characters go into a doomed battle and just wreck themselves like Daffy Duck playing Robin Hood.

And isn’t that sort of comic failure also part of the joy of games?

A couple of thoughts:

First, I confess to doing a Google Image search to see what a "Gauloise Blonde" looked like (recalling the "Platinum Blondes" of the 1920's), only to find a lot of pictures of cigarette boxes, and no ladies. Well, at my age, I really shouldn't be messing with either kind.

Second, I recalled the French "Savate" fighting style, and its likely influence on the game's approach to combat. I haven't seen any of the recent boxing simulations, but in actual boxing there is considerable emphasis on blocking, dodging ("slipping"), and parrying in addition to just hurling aggression. A common definition of the "Sweet Science" is "the art of hitting without getting hit". This adds a welcome tactical dimension to computer gameplay.