Game Writing Conundrums: Death of the (Interactive) Author

Whose story is it: the writer's or the player's?

I’ve been doing this game writing and narrative design thing for a while now. So long, in fact, that there weren’t really college courses in game design when I was a student. Instead, overachieving nerd that I was, I got a Bachelor of Humanities and Arts in Creative Writing and Interactive Fine Arts.

And yes, it did take me a while to actually get a paying job using my degree, thank you. I even had to teach myself Flash — little did I realize that being able to teach yourself how to use new engines was, itself, surprisingly good practice for working in games.

But even more, it also means that I came to a lot of game design and writing from the well-rounded and academic theory-and-critique heavy background that’s sometimes called a “classical education”. And one thing that stuck with me was a particular theory of literary critique called “The Death of the Author”.

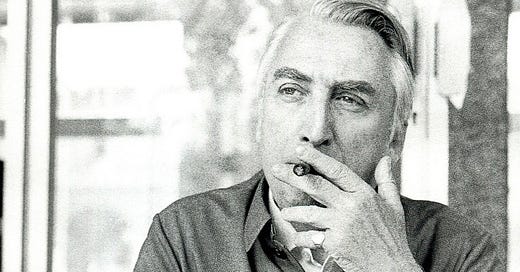

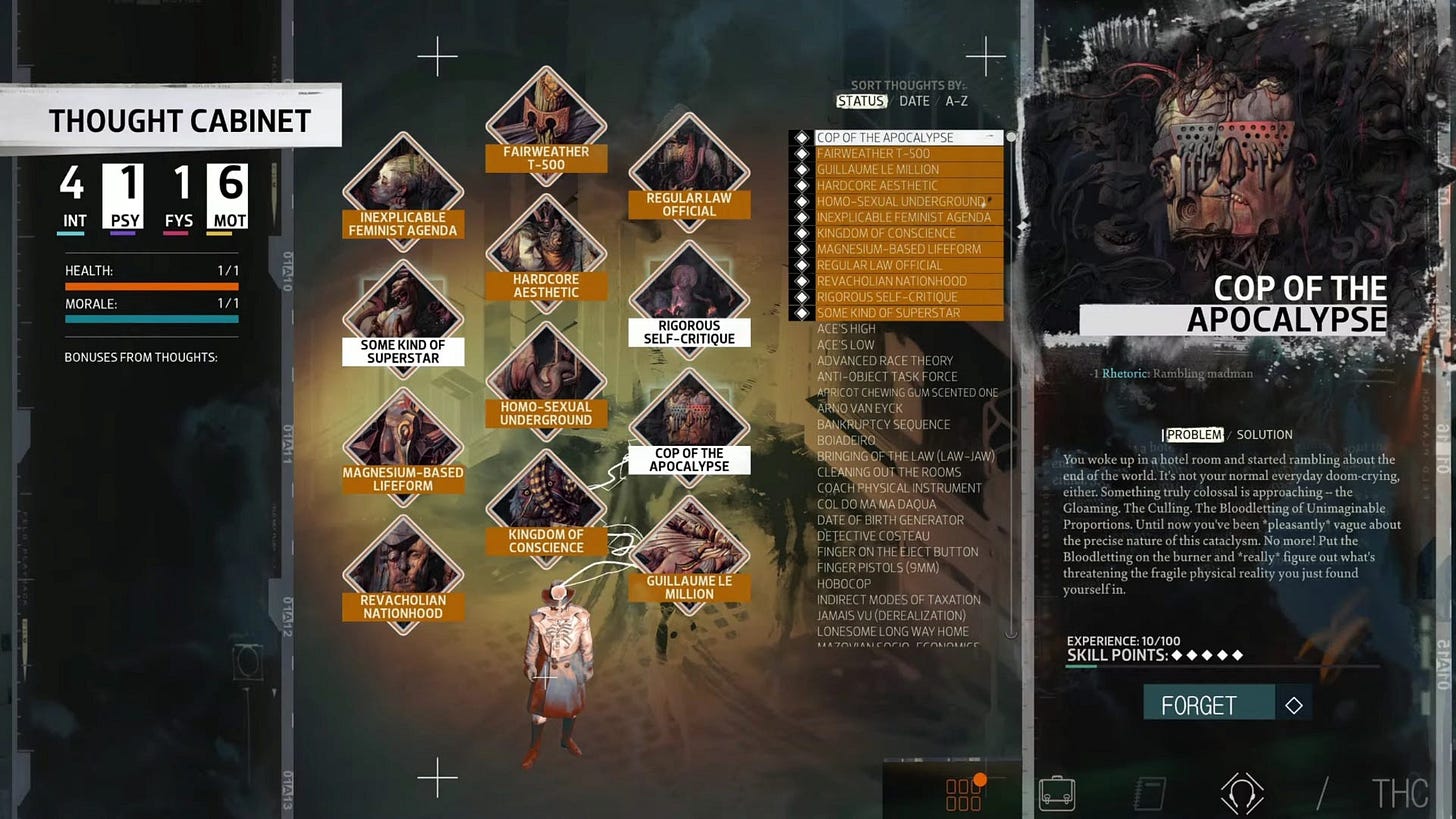

First proposed in 1967 by Roland Barthes, the short version of the theory is that the author of a text is not the sole authority on its meaning — as truly understanding intent is difficult, even for one looking back on their own thinking — and that a text’s essential meaning lies more with the audience reading it at the time. In this fashion, the “meaning” of a novel might change over time as difficult generations approach it with different cultural interpretations, rather than it always being set in stone based on what the author claimed about it at the time of its creation.

Now, this is a fairly standard postmodernist approach to interpreting art, deconstructing the idea of a singular “official” meaning and opening it up to more subjective interpretations. If you recall my earlier post about how to appreciate art, you can probably guess I have a more complicated approach to the subject.

Suffice to say, this theory is not generally popular with authors. Or, more to the point, not with auteurs.

But when we’re talking about writing for interactive fiction, where the player can control how the story plays out, this theory feels much less theoretical.

The Paradox of Narrative Control in Interactive Fiction

For game writers, there’s no such thing as perfect control of the story.

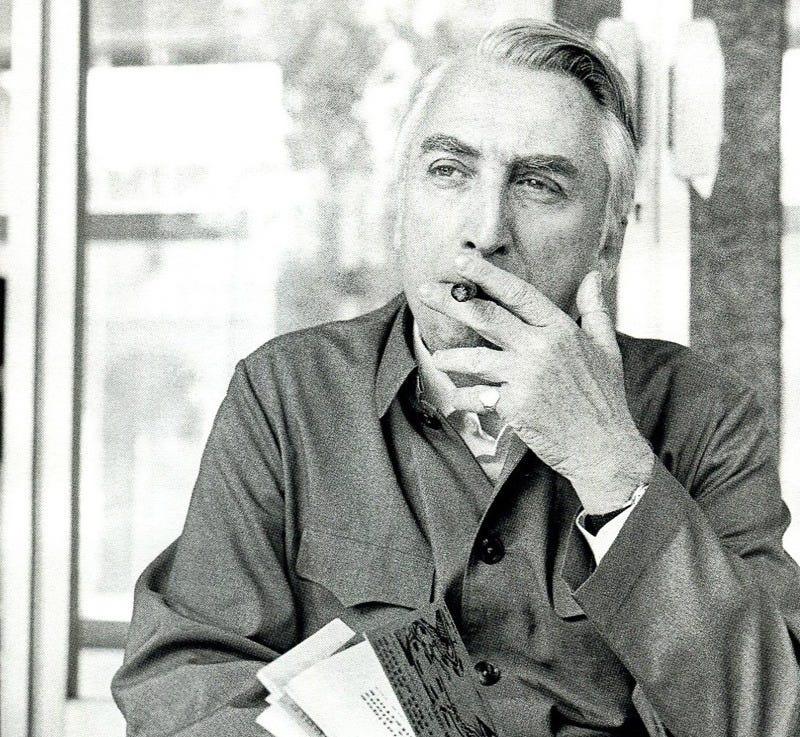

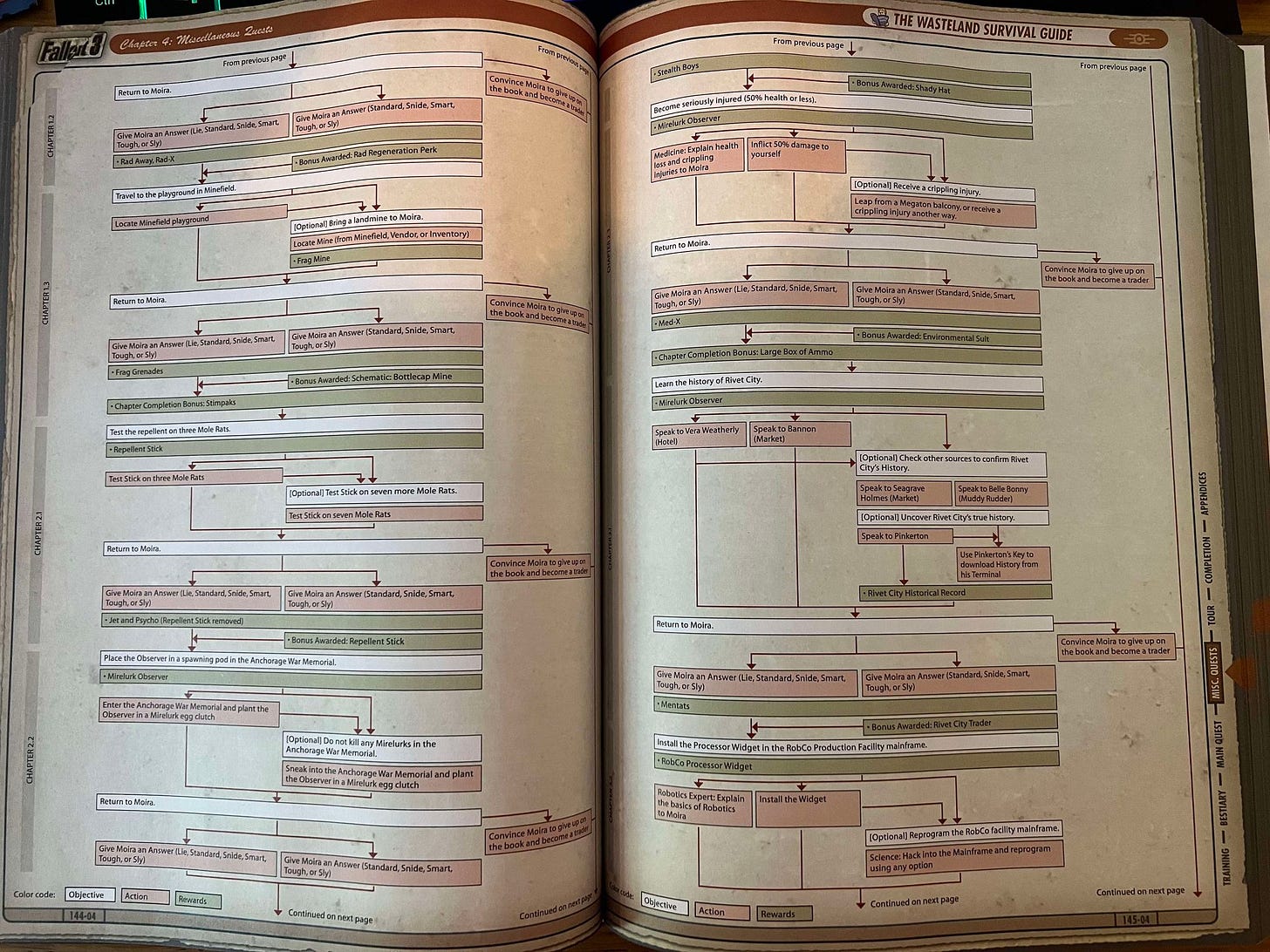

This is manifestly true for the sort of open-world RPGs that I’ve called home for most of my career, where wildly branching storylines and high player agency mean it’s difficult to even predict where a player will take their story, much less to force them into a singular interpretation of it. When you write 40,000 lines of dialogue, the player has a lot of material with which to build their own story.

But even in the most strictly-structured game with little to no player agency (ie, where the player is railroaded, the sort of thing occasionally called a “ghost train ride”), the experience of that story is still heavily up to the player — from the interpretation to the pacing to the performance to just relying on the player having the skill (and interest) to continue it at all.

For a game writer, that loss of direct control just comes with the medium. Still, for some types of game auteurs, it’s infuriating to know that a player can “play the story wrong.”

This completely misunderstands how the medium works. I’d argue it’s one of the more pervasive holdovers from the era when games took their cues from movies — the medium that gave birth to the concept of auteurism. The interactivity is the defining element of the medium of games, and resenting it for allowing players to undermine your story just raises an important question:

Whose story is it?

The Story of the Game

Now, not every game particularly cares about telling you a story. And that’s fair — we don’t need a grand storyline about Pac-Man fighting for his family to enjoy the experience of chomping pellets and ghosts. There are some lovely stories in gaming, but it’s rare for those games to triumph on the ground of their stories alone.

As I’ve said before, a good game has a toy as its heart. But, as anyone who’s known (or been) a kid knows, you can’t play with a toy without telling yourself a story about it, in one way or another.

And ultimately, that’s the important story of a game: the story that the player is telling themself while playing. This is just how humans work — we process our experiences as stories, with heroes and antagonists, lessons to learn, etc.

A game writer who gives the player any freedom at all can try to influence it, but mostly we’re just setting the outer boundaries of the story and the elements the player can use in telling their own story.

Canon: a Metamodern Multiversal Mess

It’s not just interactive fiction that has raised these questions of authorial supremacy, either.

Between huge franchises that involve multiple authors, IPs that blend multiverse storylines, and the rise of fan fiction that rivals the popularity of the original text, we’ve seen more and more cases where ownership of a story is divided, at best. Ultimately any argument about what is and isn’t “canon” comes down to that question of authorial supremacy.

Any Star Wars fan has seen the battles fought over which movie, series, game, or book counts as cano, and what degree of canon. Longtime showrunner for Dr. Who, Steven Moffat, memorably declared that “It is impossible for a show about a dimension-hopping time traveller to have a canon”, and that therefore any Dr Who fiction is equally canon — you just may not have seen the other stories that explain how they fit in.

Even The Elder Scrolls games have found a way to incorporate the wildly varying stories players can create into a sort of multiversal canon that incorporates all players’ different experiences as true. My favorite is the fact that every playthrough of The Elder Scrolls 3: Morrowind is just one of infinite realities that the daedric prince Azura experiments with in order to find a suitable savior for the world that lives up to her own prophecy.

So technically, all playthroughs of Morrowind are canon, from the heroic one where you were the Best Nerevarine, to the one you just ran around and collected sweetrolls, to every weird mod you hooked on (although we can assume other, less savory daedric princes were behind some of those mods).

Every player’s story is real. It all counts. Even if it’s absurd. Maybe especially then.

The Birth of the Player

When Barthes wrote about his theory, he said “the birth of the reader must be at the cost of the death of the author” — that the agency of the reader to interpret a text requires a yielding of agency from its original creator.

As I mentioned earlier, this is a very postmodern sort of critique, in that it rejects the idea of a singular, prescriptive meaning (a “modernist” position) in favor of multiple, individual deconstructions of a subject (a “post-modernist” response). And while I’m still in the process of writing a larger article on the evolution of modernism, postmodernism, and metamodernism over the last century of culture, I’ll just point out that this twist from interactive fiction suggests a more metamodern theory that synthesizes the two prior two positions.

Here, the player is in conversation with the author. Less “the author is dead” and more “the author is moderator.”

In these media, the author (or IP owner) is not the final arbitrator of what is true in the work, but the moderator of a discussion between countless authors and contributors.

The author can set the tone for the story, along with the boundaries of what is considered acceptable and what sort of material gets used in the setting, but the exact stories created within that framework is never fully in their control.

Different authors will be more or less lenient with their control, but when it comes to interactive fiction, the player must always have a voice in the conversation. And the more they feel heard, the more invested they’ll feel in the story.

Their Story, Your World

So, does this mean that game writers are unimportant in interactive fiction?

Not at all! It just means that we need to adjust the scope of our vision in storytelling.

We must focus less on telling a single, immutable story that must be experienced perfectly and interpreted in a singular fashion. If that doesn’t fit your storytelling goal, then I beg of you to go write a book or make a movie instead.

Instead, we must loosen our reigns of authorial control to allow for the player’s involvement and investment. We must look other the tools we use as storytellers to guide and tempt the player’s interests through a garden of possibilities, rather than to railroad them along a single path. And we must embrace thinking about the experience as a conversation between the player and our game.

Because ultimately: it’s not your story, it’s the player’s… but it’s their story within your world.