Is random generation worth it?

Infinite content isn’t worth much if it’s all meaningless

Back when I worked at Bethesda, we found we had a problem.

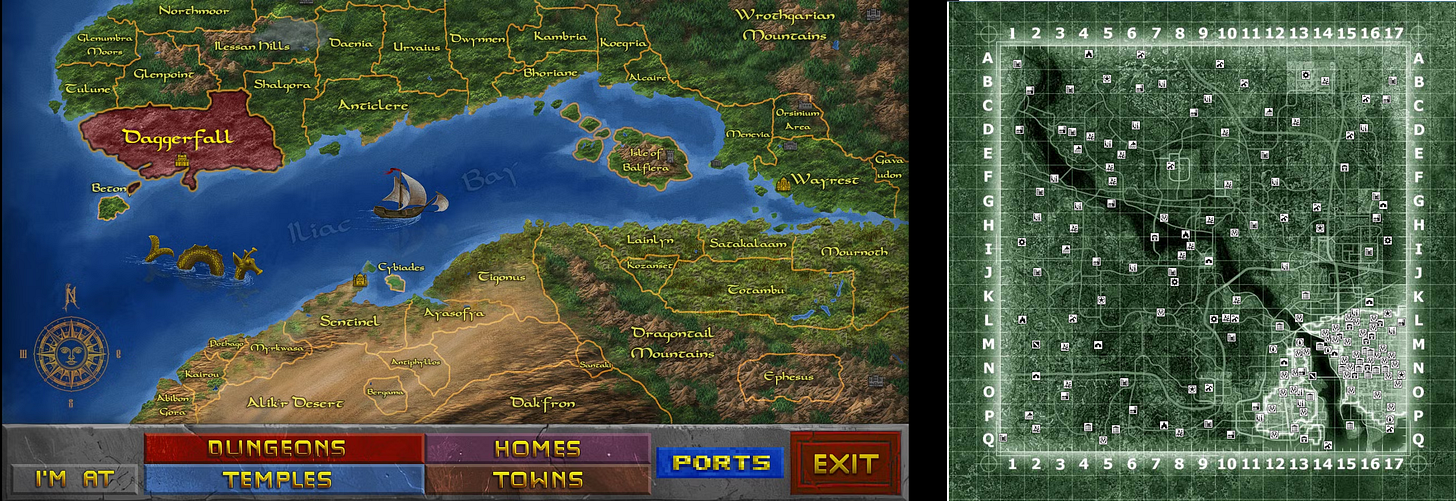

The Creation Kit allowed us to do tremendously detailed work scripting the behavior of NPCs in all sorts of different situations, reacting to internal needs and goals, and generally acting more or less like real people. This was called the Radiant AI system, and designers could spend days of work ensuring that they responded to all sorts of different situations, quest conditions, and player behaviors. And sometimes, the results were brilliant.

But most of the time, those NPC behaviors happened off-screen and the player never noticed them. If something did happen in front of a player, it was easy for them to miss the new behavior, or assume that it was one of the engine’s common, amusing glitches, rather than a cleverly-designed reaction to their own behavior.

In short, we were doing a lot of work that the players wouldn’t or even couldn’t appreciate. And along with that, such a complex system also created an equal number of unexpected and almost unavoidable problems. And as we moved onto Skyrim’s procedurally-generated quests (dubbed “Radiant Quests”), the problem threatened to multiply into another major system.

By the time I left Bethesda, the new goal was to keep this procedurally-generated content relatively simple and focused on implementing big, obvious responses to player actions — particularly in the form of generating these new minor quests. It was expected that expanding this tech into quests that the player picked up would mean the player always saw some degree of the designers’ work.

And it worked, in a way — these Radiant Quests did mean there was a never-ending stream of new minor quests for players to do, from randomly generated jobs for one of the guilds to townsfolk asking the player to avenge a dead family member. They tended to be very simple and samey, using stock dialogue and giving simple rewards, but they served their purpose to give players a reason to keep traveling around the world, and players who were into the game came up with backstory and reasons to invest themselves in the work. Exponentially more content, but with diminishing returns.

A decade-or-so later, when I heard that their new project, Starfield, was going to include near-countless worlds using a similar procedural system, I began to worry whether scaling that formula up so much was going to be worth the trade-off.

I’ll leave it up to the reader to decide if it was.

The lure of infinite content

As games have gotten bigger over the years, one of the most expensive changes have been meeting the expectations of ever-more content — whether that’s more levels, more quests, more characters, more weapons, more voice-acting, or all of the above. Open-world games, especially, have sold themselves on how big their worlds are, right down to literally comparing the square mileage of their maps.

But having a lot of content isn’t the same thing as having a lot of meaningful game.

There are times and places where having more is, if not always better, then at least important for the genre. For example, having a sheer wealth of options and seeing how they can mix and match is a fundamental promise that makes Roguelikes work, from Dead Cells to Balatro. And, as I’ve talked about recently, the promise of nigh-infinite, low-cost content is practically the entire business model of idle games.

Now, there’s a big difference between “a wealth of hand-crafted content” versus “a wealth of procedurally-generated content”. Nobody will argue that the many radically different approaches and dialogues available in Disco Elysium aren’t part of the appeal of that game — nor would they argue that it wasn’t a huge amount of work for its developers. Conversely, I don’t think anyone would argue that the mix-and-match randomness of weapons, upgrades, and level elements in, say, Megabonk — while offering numerically much more variety in combinations of content — simply doesn’t add as much depth to the experience as Disco Elysium’s numerically lesser amount of “content”. But Megabonk’s combinatorial content was also much, much cheaper to create than richly detailed, hand-crafted storylines and varieties.

Making Meaning

Ultimately, it comes down to Meaning; and yes, I’ll use a capitalized version of the term here in the sense of “a coherent plan or premise to a thing”. Ultimately, whether they’d admit it or not, most media audiences come to fiction for a sense of Meaning — not necessarily a political manifesto or a grand theory of how reality works (although those can both make for very compelling fiction), but at least a sense that there’s some guiding principles that can be understood and navigated. Considering the Meaning imbued in an experience is what most designer’s work comes down to, really. Especially for narrative designers.

When you’re hand-crafting a storyline or level, it’s easy to imbue it with Meaning (even if you don’t intend to). It comes naturally from any degree of authorial intent — even if you think you’re being strictly neutral and unbiased, you’re inevitably instilling some degree Meaning reflecting what you take for granted in the world.

But it doesn’t come so naturally to procedurally-generated content. To imbue meaning into generated content, you need to carefully think about the rules involved in generating the content, how those rules reflect your intent, and how the individual pieces of content being combined can reinforce or undermine that intent.

Kate Compton, the AI researcher and gamedev behind Spore’s creature creator, once referred to this as “the 10,000 bowls of oatmeal problem” — it’s very easy to pour ten thousand mathematically different bowls of oatmeal where the oats are in different positions, but if a player can’t tell the difference between them, then it doesn’t actually matter. You need your different procedural creations to feel different. You need to impart a sense that there’s Meaning behind them.

And I should point out that when I’m talking about procedural generation here, I’m not talking about using generative AI — that’s a whole separate conversation to be had. But for this article, I’m just talking about procedural generation as “mixing and matching from developer-generated lists of content”, the way that Starfield generates worlds from building blocks, or how Borderlands generates guns from templates and effects.

Now, procedural generation can stumble on a good combination that may suggest Meaning — for example, a piece of gear that combines a buff for deception and a debuff for empathy. Or even purely synergistic effects can suggest a deliberate intent, like enemies with random buffs that pull you in along with buffs that give them AoE auras.

But they can just as easily make for bad combinations that are either contrary to your desired intent (“I never meant to have gear that gives bonuses for killing babies!”), or simply combinations that feel nonsensical, such as buffs to magic power on enemies that don’t have magic attacks.

Ideally, a developer would take care to craft the rules and content charts in accordance with their intended meaning, and then use that random generation in playtesting or early access to find unexpectedly good combinations to promote or bad combinations to prevent. But building that random generation takes time on its own, as does manually promoting or preventing certain combinations.

Costs of infinite randomness

On paper, procedural generation looks like a great deal for developers — build a system for procedural generation, populate it with material to combine in countless ways, and let it loose to reap nigh-infinite possible variations.

But there are two big costs to procedural generation that aren’t obvious until you start playing with this system:

Players are good at recognizing patterns, and will quickly come to recognize the underlying elements you’re combining, making the randomness feel less like the bonanza of “ten million possible combinations!” and more like what it really is, “one pick each from seven lists of 10 options each.”

With countless possible combinations, you run into lots of unexpected bugs as different systems get mashed together in ways you didn’t necessarily plan for.

Issue number one is fine enough: modern players are coming to recognize what procedural generation means, and aren’t automatically impressed by big numbers of possible combinations anymore.

But issue number two is the real problem, because strangely enough, game producers don’t seem to have picked up on it as quickly as game audiences picked up on the first issue.

You see, relying on procedural generation looks like it’ll take a lot fewer developer-hours to create a wealth of content, because you can make and test each element on its own and then combine them in gameplay for big numbers of raw content. But what it doesn’t show is that this will also lead to an unpredictable number of bugs as some of that random content fails to play nicely with other parts of that random content.

So when a producer decides to use procedural generation, they need to factor in much more bug-fixing time towards the end of production to handle these unpredictable results. But I haven’t seen a lot of major studios doing this, and instead those fixes get pushed back to post-release patches.

How to make randomness pay off

Procedural generation can be a tremendous boon to a game, but you have to know how to make use of it properly.

First, from a production point of view, you’ll need to schedule extra time for late-production refinement and bugfixes. All those millions of combinations are going to require much more playtesting to find the new and unusual ways they can break, and you’ll want to add some degree of manual tweaks to the combinations of elements that are preferred or prohibited.

Ideally, this should be done in an early-access/open-beta framework, as such high numbers of combinations will require as many testers as you can expose to it. Listen to their feedback, check their telemetry and metrics, and find what’s sticking out as a problem. This is a vital step of balancing the game, and you should make that clear to the people who are acting as playtesters — all the better to draw them into the fold of making the game as good as possible.

But, in the larger design/craft point of view, the way to get the most out of procedural generation is the same as most things related to narrative design or con artistry: get the players invested in the experience first, and their imaginations will do the work of filling in the blanks and smoothing over the cracks.

In practice, that means the game should lead with your best, most compelling, most handcrafted work first, to really give the players a taste of what the game’s best possible experience should be. Then, you can slowly introduce the procedural elements, ideally alongside other handcrafted bits that tie into them. And as long as you’ve done the work of testing and balancing and manually tweaking the procedural content charts to stay in keeping with the game’s overall tone, it’ll fit in smoothly with the player’s ongoing experience.

Because if you prime a player with a sense of Meaning early on, and they enjoy it, they’ll look for it in the rest of the game. And if you’ve built your procedural generation well, they’ll be able to find no shortage of it.

"But having a lot of content isn’t the same thing as having a lot of meaningful game."

This needs to be plastered in every developer's office. This is why many gamers prefer 20 to 30 hour experiences (maybe even shorter) over 100+ hour open world epics. 100 hours of forgettable content isn't entertainment.

I was hoping you'd bring Borderlands into this discussion, because it always felt like the best example of how procedural generation doesn't always work. I remember coming across so many pointless guns in the original that I questioned if it maybe was meant to be an inside joke.

And completely agree with your breakdown on how to best utilize procedural generation. It shouldn't be at the forefront of the experience, and I often don't bother with games that so heavily market their game for its procedurally generated content. To me, that rings of a game where I will spend a lot of time going, "Why does this thing even exist?"