Back in the promotional run-up to Netflix’s Wednesday series, there was minor controversy when the casting was announced of Luis Guzman as Gomez Addams. I was confused because many of my younger friends were aghast at the early pictures, feeling it wasn’t accurate to the beloved character.

Personally, I withheld judgment until the show came out (and since its release, I feel that position has been vindicated). But I found the choice to be exciting — not just because Luis Guzman is a fantastic actor who I trusted do it justice, but because I had grown up reading the original comics, and felt his appearance captured a ghoulish element of the comics that had disappeared in later versions.

But more to the point, it made me wonder: what determines a “correct” interpretation of a fictional character? Especially once the original creator is dead (or even before then, depending on your feelings about the death of the author).

Taking Up the Mantle

When you’re creating a new performance of an iconic character, you face a difficult balancing act: you have to know what elements are considered fundamental to a character, but you also need to find a unique aspect of them to play up and make your own.

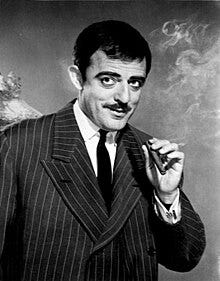

In the case of Gomez Addams, there are a lot of past greats to consider: the macabre comics by Charles Addams, the kooky spooky patriarch of John Astin, the debonair madman of Raul Julia — to say nothing of less famous portrayals by Tim Curry, Nathan Lane, and a variety of cartoons and games since then.

Triangulating an essence of the character from the most beloved of these performances would be difficult for anyone — much less while staking your own ground. Sometimes, though, you get help from the original creator.

Character Rules

When an author knows they’re creating a character for use by other authors, or in perpetual syndication, they’ll lay out a definition of the character. Sometimes this can be as simple as a descriptive paragraph, or as strict as a set of rules — as Chuck Jones memorably did for the Roadrunner and Coyote cartoons in his autobiography “Chuck Amuck: The Life and Times of an Animated Cartoonist”.

Most modern shows (and some forward-thinking games) will create a “show bible” where the leads lay out the defining rules and themes of their worlds and characters, for use by the assorted artists, writers, actors, and directors to keep their work true to the overall vision of the show. Similarly, animators almost always have to develop an “art bible” to coordinate the work of the many artists who have to match the same style for an animation. These can also be fascinating reads for fans of the show in question, presenting insights into core themes and mysteries.

Still, shows that run for a long time can find themselves outgrowing their original bibles, like this original show bible for Adventure Time, which was almost immediately outdated by the end of the first season. Let this be a good reminder that any successful show will grow beyond your original interpretation, and that a show or art bible must be a living document that grows along with it.

When ABC was creating the sitcom version of the Addams Family, they brought in Charles Addams himself to help define the characters. Addams hadn’t even named most of the characters in the early comics (which is why they had become known by his name alone), so much of this was written after the characters had been field-tested and refined a bit.

“Husband of Morticia (if indeed they are married at all), a crafty schemer, but also a jolly man in his own way. Tries hard to be father and teacher to the children, though sometimes misguided— we can depend on Morticia to straighten him out. Sentimental and often puckish—optimistic, he is full of enthusiasm for his dreadful plots. He is dressed in a tight double-breasted striped suit and is sometimes seen in a rather formal dressing gown. The only one who smokes—though Pugsley can be allowed an occasional cigar.”

— Charles Addams, as quoted in “The Addams Family: An Evilution”

We can certainly see those traits in every version of the character: the enthusiasm, the dedication, the sentimentality. Astin may have played up the jolly puckishness, and Julia added a manic flair and charm all his own, but they all stayed true to the author’s original understanding of his character. Similarly, Guzman’s portrayal captured the character’s optimism and utter dedication to his family, even if it was with a more laid-back energy than previous interpretations (a choice fitting for portrayal of an older version of the character).

All of these performances felt true to the character to most audiences, and as such, have gone on to make a more robust understanding of the character in a new generation — which will, in turn, inform future interpretations of the character.

But what happens when a portrayal of a character misses the mark for whatever reason? Or when a long-running character faces a new generation of authors and audiences who connect in different ways?

Going Out of Character

In the pantheon of characters who have outlived their original authors, there’s no shortage of interpretations that struck audiences as wrong or untrue to the characters they had come to love so much.

Comics and other nerd fandom are especially full of this, both because long-running characters may find themselves being written by several different authors at the same time between multiple books, and because their fanbase includes extremely passionate and vocal critics who may have bonded with different interpretations of the character at various points in their life.

(The only place with more passionate fans reacting to more disparate interpretations of a character is in the realms of mythology and religion, where literal wars have been fought over different interpretations of fictional characters and their core messages. But for now let’s stick to the less controversial nerddom of comics.)

Superman may be a prime example of this dynamic, as decades of constant content creation have seen countless interpretations of the character in the hands of authors and directors who didn’t appreciate the core of sincerity and good-heartedness that lies behind the superpowers. Or, in the case of Zak Snyder, Frank Miller, and others, authors who seem to actively dislike those traits.

When we see these “aberrant” interpretations of characters, it’s usually the professional critics and long-term fans in the audience who are most vocal. And although divisive interpretations can lead to long-running discourses and schisms, clear misinterpretations lead to broad rejection of that particular interpretation (even if it appears in an otherwise popular work). When a new author takes up the character, these audience responses will inform their decisions for the character.

Personally, as someone who grew up watching decades worth of old Dr. Who episodes, my response to a disappointing take on a character is “wait a while and you’ll get a new one”. Perhaps a perspective that comes from age, and definitely a privilege you only have when a beloved character is a capital-I Institution, but one that leads to fewer bitter arguments at least.

These characters and these franchises aren’t going to disappear, especially not in our modern era of “already-built IPs” and “courting established audiences”. I don’t think there’s been a reboot yet so bad that it permanently killed an existing franchise. At least not so bad that some mad genius couldn’t pick it up again and breath new life into it at some point in the future. Particularly if and when some production company is rooting around for a known IP to reboot for cheap.

What Endures, Defines

Because ultimately, the only way that a fictional character can maintain their longevity beyond an author’s lifetime is from the love of the audience — whether that manifests as successful sales, critical acclaim, or cult popularity, something about the character must connect with an audience outside of the author alone. And once a fictional character has made that step into immortality, there will always be someone looking for the next way to embody them for a new audience.

To return to the Addams family, what are the traits about them (and Gomez in particular) that make them so unique and beloved with audiences?

For Gomez, I see a lot of people saying it’s his complete and consuming adoration of Morticia — and that’s not wrong, but I think that’s not the whole of it. He has that same enthusiasm for everyone and everything he loves: his family, his hobbies, everything. Whether he’s a suave gentleman, a weird kook, or a creepy ghoul, Gomez has a ferocious heart and utterly unashamed sincerity.

In fact, this may be the core of the Addams Family as a whole: despite their dreadful mien, they are wholeheartedly sincere and loving, making no excuses and never hiding who they are. It might even explain why they have such an enduring appeal with queer audiences and any other community that has had to face the prospect of hiding who or what they love. They are who they are, they see nothing to be ashamed of, and they dare the world to raise an objection.

Is that an aspect that Charles Addams intended in his original definition of the characters? It’s not explicitly labeled (and may even go against the “crafty schemer” description), but it’s come to be one of the beloved traits of the entire family. The author certainly couldn’t have predicted how it would connect with people that came after him, but audiences and performers have ensured that it will forever be a truth about the character — fictional or not.